Executive Profile

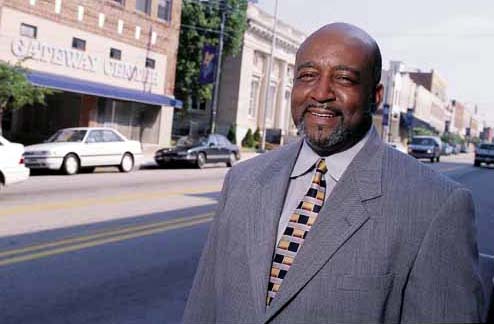

Abdul Rasheed of N.C. Community Development Initiative

By Suzanne Fischer

As the clock ticks off the final

seconds of the 1965 high school basketball game in Raleigh, one player exults in the

contributions he has made to his team's winning performance. Spectators in the stands have

worked themselves into a frenzy.

But the crowd isn't roaring approval; instead, the fans are

viciously booing. And Abdul Rasheed, the young man with the amazing jump shot — and

the only black player on either team — needs a police escort to escape the gym

unharmed.

“People were really angry at my performance, which was a

good one, . . . that a `colored boy,' as they called us then, had helped my team win the

game,” Rasheed recalls. “That was just symptomatic of the attitudes that were

prevalent during that time.”

Fast forward almost 35 years. Rasheed, now 50, is founder,

president and CEO of the North Carolina Community Development Initiative (NCCDI). The

organization serves as an intermediary channeling funding and providing training,

technical assistance and other services to Tar Heel community development corporations

(CDCs). The organization's mission is to help low-resource communities whose fortunes have

not been as golden as the state's three metro areas.

Warm eyes and a gentle smile don't conceal the strength of

Rasheed's resolve, a determination built over a lifetime of proving himself under

circumstances sometimes less than ideal.

Born in 1949, Rasheed grew up in Henderson in a tight-knit and

supportive neighborhood rich in ethics and spirit if not in actual wealth. The values of

hard work and self-improvement, he says, were just part of the fabric of the community,

where he was raised by his grandmother. “She was wonderful in terms of her nurturing

spirit and absolute insistence on the pursuit of education and the whole question of

excellence. I'm deeply indebted to her for that kind of push and inspiration,” he

says.

He remembers his childhood as fairly typical of “young

African-Americans born into that era of segregation and from pretty meager

beginnings.” All that changed dramatically when Rasheed was one of a handful of

students in Vance County recruited by town leaders and local civil rights activists to

integrate the high school. Despite his grandmother being “scared to death” and

his hesitancy to leave behind friends and a comfortable, accepting environment, Rasheed

agreed to go on the urging of his teachers. Looking back, he's not sure that the school

provided any better learning opportunities than the schools in which he'd grown up, but he

believes that integration helped move his community forward.

“I don't regret my decision. It helped shape who I am as a

person. Early on I became exposed to bad attitudes but also to good people who didn't have

anything to do with race,” he says. “And I learned that I could take to heart

what my grandmother had been telling me my whole life: that I was just as good as

anybody.”

Despite being recruited by Villanova and several other NCAA Division 1-A schools for

his basketball prowess, Rasheed chose to attend Elizabeth City State. After his difficult

high school years, going to a small, predominantly black college seemed the right choice

and is, indeed, one he remains glad he made. Dr. Marion Thorpe, chancellor at the time and

then just 36 years old, served as a role model for Rasheed and other young men at the

university. It was Thorpe who encouraged Rasheed, after graduating in 1971 with a bachelor

of science in business education, to attend law school at N.C. Central University.

Law school proved to be a too great a financial burden, and after

one year there Rasheed accepted a fellowship that gave him a full ride to Trenton State

College in New Jersey. In 1974, he earned a master's degree in counseling and personnel

services and headed back to North Carolina, intent on returning to Central and law school.

But after leaving Trenton State, Rasheed married Marolyn, whom he'd met at Central, and

the couple “had two sons before you knew it,” he says, grinning widely.

“That was the end of school for a while. I had to get a job!”

He taught for several years in the community college system but

ultimately landed at Legal Services of North Carolina, a move which helped him discover

his calling in community development.

“Legal Services afforded me the opportunity to become

familiar with the state's low-wealth areas and to appreciate the need for more proactive

strategies to help people in poverty,” Rasheed explains. As important as he believed

the work to be, he was frustrated by the lack of permanent solutions for people and

communities in need.

In 1988 he left Legal Services and founded the North Carolina

Association of Community Development Corporations, which attracted financial and human

resources to help CDCs statewide achieve their goals.

After five years with the association, Rasheed recognized that to

accomplish increasingly sophisticated and complex economic development projects, CDCs

needed even more money and more professional technical assistance. He sought and received

a $75,000 planning grant from the Ford Foundation, spent some time researching the needs

of CDCs across the state to see how he could help fill the gap and, in January 1994,

incorporated NCCDI.

Andrea Harris, executive director of the N.C. Institute of

Minority Economic Development, has known Rasheed since kindergarten. She likes to tell the

story of an earlier project he took on: “At that time Abdul wasn't working nearby,

and I said `you need to come here and provide a little leadership at home,' and he agreed.

He went around the community to see what people lacked, and they told him they needed a

financial institution.” Not quite knowing how to go about it, Rasheed leapt in with

both feet anyway. After a lot of legwork and a few mistakes, he helped the community get

its first credit union. “The important thing is that Abdul didn't know just what to

do, but he was willing to take a chance,” Harris says.

But by the time he'd founded NCCDI, Rasheed had years of

community development work and education under his belt, selling points he used to gain

the trust and resources of a variety of investors, including state government, banks,

foundations, and private corporations.

NCCDI performs three main functions. First, it serves as an intermediary, attracting

investments and passing those resources to local CDCs in the form of loans.

“We're a lender of last resort,” Rasheed explains.

“Our loan limit is $200,000, so we specialize in gap lending to projects that have

gotten all they could from traditional lending sources and are still short.”

Second, it acts as an operating foundation, making grants of its

own. In 1999 NCCDI will have made $2.6 million in grants to about 22 organizations.

Recently, First Union loaned $1 million, which NCCDI will relend to projects taken on by

CDCs in targeted communities. The First Union loan was the second half of a matching loan

from a $1 million deal Rasheed closed a month earlier with Bank of America.

Third, NCCDI provides training and technical assistance, offering

courses and consultation to CDC staff and other community leaders and local business

people. And in cooperation with St. Augustine's College in Raleigh, the organization is

introducing a bachelor's degree in community economic development, the first of its kind

in the Southeast.

He's excited about the impact the organization's made in such a

short time. It's raised $20 million over the last five years and turned that into $100

million in development, including residential real estate, commercial real estate, light

industrial sites and credit unions.

“What's most important to me is that this type of work is

not a Band-aid. Economic development helps people sustain themselves, to be independent.

We work within the communities to create jobs and businesses and other wealth accumulation

strategies to help develop the larger macro economy. This way people can permanently

transition themselves out of poverty. It's consistent with the American dream,”

Rasheed explains. “And we're taking a business approach . . . making it a good

proposition for all involved.”

Before the organization agrees to help back any projects, Rasheed

and his staff carefully review all proposals to make sure they were conceived on sound

business principles.

One recent project is a new shopping center in a depressed area

of Charlotte. Anchored by a Food Lion and a major drug store and home to several smaller

businesses of local entrepreneurs, the center, upon opening, created 100 new jobs for

people in the neighborhood.

Another project Rasheed speaks of with excitement is a new

housing development in Wilson. The Wilson Community Improvement Association secured

resources to purchase the land and was awarded community block grant funds to lay down the

infrastructure of roads and lights. Then the group worked with community citizens,

offering credit counseling and advice on saving for down payments so that they could

qualify for mortgages from traditional lenders.

“We gave them an operating grant to help them staff the

project and manage the process. They worked with BB&T, too. And now,” Rasheed

says, beaming, “there are 100 plus new homes that grew out of an inactive cornfield.

There are 100 plus families that now own their own homes. And they're taxpayers to the

city and county of Wilson and the state of North Carolina.”

IN Rocky Mount, the local CDC developed eight downtown buildings into a mixed-used

project; offices and retail occupy the street level, and the second and third floors were

converted into 24 units of senior citizen housing. The CDC secured a grant from NCCDI,

which also provided a loan that served a secondary function of helping attract money from

the city and Centura Bank.

“This is going on from Asheville to Wilmington to Camden

County,” Rasheed says. “It's a state-wide initiative. I have to say that we've

only scratched the surface. If we had even more resources —we're trying to raise $40

million in the next five years — we can double and triple our output.”

Rasheed praises the support that his organization has received

from the state legislature, which has put NCCDI in the base budget so that it receives a

biennial appropriation. Other major supporters include the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation

— which gave $2.25 million, one of the largest grants in its history — the Ford

Foundation, Kenan Urban Enterprise and many of the state's largest banks.

Drumming up this kind of support and managing the day-to-day

operations of the initiative demands a lot of time on the road and a multitude of

meetings.

His energy and passion for his work are legendary. State Sen.

Frank Ballance (D-Warren) has known Rasheed for about 10 years, and the two serve on

several boards together. “The word that comes to mind immediately is

commitment,” Balance says. “When he takes on a job, he gives 100 percent. Some

people are in a job to make a living. That doesn't apply to him; he loves what he's doing

and he's happy to make a difference.

Ballance admires the success Rasheed has had in protecting his

organization when budget crunch time rolls around in the General Assembly. “We

couldn't give him quite what he asked for, but we try because we believe that what he's

doing is important and because he's got such a good track record. He shows he can take tax

dollars and leverage that to attract even more money for good causes . . . and we love

that.”

Harris applauds his courage: “He's got such a good spirit

about him. The kind of things he does are cutting edge. North Carolina is on the forefront

of this movement. That can be a little frightening at times, and he'll acknowledge that

without losing his footing.”

Rasheed is quick to share the praise with his staff of 11, the

CDCs the organization supports, his diverse board and a dedicated group of volunteers.

“I'm blessed with talented and professional people around me,” he remarks.

“What we do would not be possible without their commitment to this work. They're

passionate about this job and I have every appreciation for them.”

He holds leadership positions on a number of economic development

councils, is a trustee of Vance-Granville Community College and serves on the advisory

board of First Union.

In his time away from work, Rasheed has been trying to improve

his golf game. “I won't go so far as to say I `play,' but it's my relaxation and

escape. I like to be out in nature and try to compete against the course . . . and

sometimes other players.”

His family (a “small tribe,” he calls them, chuckling)

includes his wife, Marolyn, and two daughters and three sons ranging in age from 16 to 30.

He's traveled extensively to West Africa, Italy, England, Amsterdam and the Caribbean. He

also reads, mostly nonfiction; current bedside books include biographies of B.B. King and

Nelson Mandela.

Mostly, though, he feels blessed to be in a profession that's

personally gratifying and professionally interesting and challenging.

“Eighty percent of my job is creating confidence and raising

resources and building relationships with potential investors. I show them how it makes

strategic sense for them to invest with us, that by working with us they can do good

and

good business.

“We're on the right side of the issues. I get to help people

be the first in their family history to buy their own home or their start own small

business. What can feel better than that?”

Suzanne Fischer can be reached at sfischer@nccbi.org

or by calling 919-836-1412.

COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL. This article first appeared in the October 1999 issue of

North Carolina magazine. |