State of

Banking

De Novos

Small Cogs Help Turn a Big Economy

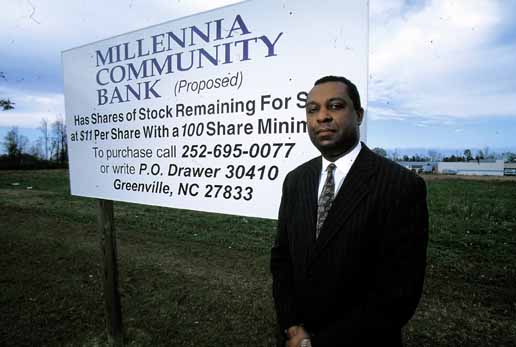

Below right: Butch Congleton

stands in front of a sign announcing Millennia

Community Bank in Greenville. Photo by Dan

Crawford

N.C.

banks ranked by assets

N.C.

banks ranked by deposits

Addresses,

links to all N.C. banks

By Ed Martin

As

the rain drummed on his mother's roof, Butch

Congleton fretted. He and his family had fled

north to Robersonville when the Hurricane

Floyd-swollen Tar River isolated their Greenville

home. They were safe here, but his dream wasn't. As

the rain drummed on his mother's roof, Butch

Congleton fretted. He and his family had fled

north to Robersonville when the Hurricane

Floyd-swollen Tar River isolated their Greenville

home. They were safe here, but his dream wasn't.

Congleton remembers when

the dream first came to him growing up in

Robersonville as one of eight children. Sometimes

he would go with his father, who owned two

downtown stores, to the Wachovia Bank. When he

was 8, he looked up at the banker and

said, “One day, I'm going to be a bank

president, too.”

Thirty-two Septembers

later, Congleton was about to know if his dream

would come true. He was scheduled to appear

before the North Carolina Banking Commission to

hear its decision on granting a charter for his

proposed Millenia Bank of Greenville. But roads

west were cut off by Hurricane Floyd floods, and

when he tried to hire a helicopter, all but

rescue flights were grounded. The postmaster

mentioned that some back roads were open, so

Congleton decided to try looping north, then

along the Virginia line, and back to Raleigh. He

drove off into the rain, skirting washed out

bridges.

The usual 90-minute

drive took five hours. Arriving at the Banking

Commission for his do-or-die meeting, Congleton

realized some of his directors, who were needed

to provide valuable backup and moral support at

the hearing, were stranded in flood shelters. For

an hour or more Congleton faced the panel of 15

veteran bankers and others who grilled him on

Millenia's business plan.

The grueling examination

is one that all wanna-be-bankers must pass to

receive their charters. “You're not really

standing naked before the world. You just feel

like it,” says Wes Sturges, president and

chief executive of First Commerce Bank of

Charlotte, chartered in 1996. “Your

knees,” adds Thad Woodard, president of the

N.C. Bankers Association, “are knocking like

when you got married.”

Congleton told the

commissioners that his customers would be mostly

rural, lower- and middle-income. And, he added,

“the kind of mom-and-pop businesses I grew

up with.” They deliberated, and gave him

their blessing to start — as soon as he

raised $5.5 million from investors.

Millenia Bank of

Greenville was born. It would become one of 35

new Tar Heel banks created this decade, tops in

the nation.

It joins the ranks of

community banks sprouting at an unprecedented

rate. Since 1990 investors have pumped $200

million into new North Carolina banks, money

which usually comes from small investors.

Congleton needed 2,000 investors, mostly school

teachers, factory workers and small-business

owners to put up an average $2,200 each to create

the first black-owned bank chartered in North

Carolina since 1971.

Usually, it's a safe

investment. Many of the 35 new North Carolina

banks have returned profits in as little as a

year. First Commerce Bank went from nothing to

$88 million in assets in three years and is

highly profitable.

Typically, they must

work hard to win customers, as the two-year-old

Bank of Asheville did for Laurey's Catering.

Although highly popular, with annual revenues of

over $1 million, the restaurant was in trouble

just over a year ago. Even before an employee was

diagnosed with hepatitis, which cost the catering

and gourmet-meals-to-go shop unexpected thousands

of dollars in lost sales, owner Laurey Masterton

had let growth get away from her. Cash flow was a

trickle, and bills mounted.

Bank of Asheville helped

her consolidate her debt. “(Bank president)

Howard Montgomery would come by every month and

spend hours and hours going over our books,”

says Masterton. “He and his loan officer

would help me spot trends and organize my balance

sheet, and they helped me juggle long-term and

short-term debt. They saved my business

life,” Masterton says flatly.

Experts say service like

that is a big reason de novo banks, as the

industry calls those starting from scratch,

flourish in North Carolina. “Growing banks

is like growing tomatoes,” says Tony Plath,

director of the Center for Banking Studies at UNC

Charlotte. “With tomatoes you need water,

fertilizer, sunshine and a favorable environment.

With banks, you need good infrastructure, a good

economic environment and good bankers. North

Carolina has them all.”

When it comes to new

banks, “We're more prolific than any other

state,” adds Woodard. Big banks control 90

percent of assets, but community banks make up

more than 120 of his 134 members. “They've

proliferated from Elizabeth City to

Hendersonville, and they're still coming.”

Insiders can name another eight de novo banks in

the works.

Underlying the formation

of each is usually a drama like that of

Millenia's Congleton. Only the details and dollar

amounts differ.

In the age of overnight Internet successes and

virtual companies, banks are created the

old-fashioned way. The process is part Norman

Rockwell, with Rotary Club networking and

cookouts and fish fries under shade trees in back

yards. “How about a prospectus with that

burger, neighbor?” But it also requires

months of financial finagling, grueling work and

high-stakes intrigue.

Investors with deep

pockets are limited and timing is critical.

Sturges launched his Charlotte bank in 1995 and

needed to raise $8.8 million. Two weeks later, by

coincidence, First Federal Savings & Loan of

Charlotte converted to public ownership with a

$300 million stock sale. Investment money dried

up overnight and it took Sturges a year longer

than expected to raise his startup capital.

But there's another

reason. Virtually all de novo executives cut

their teeth with large, existing banks. Many,

says Raleigh lawyer Tony Gaeta, who has handled

legal work behind a dozen new banks, put in

months or years of groundwork while still with an

existing bank. Only at the last minute do they

synchronize public announcement of the new bank

with their resignation from the old.

A case in point is James

Bolt, president of First Trust Bank in Charlotte,

which was chartered in May 1998. When Bolt needed

a preliminary conference with State Banking

Commissioner Hal Lingerfelt, Gaeta arranged for

them to meet blocks away from the commission

offices. Bolt was a high-profile Central Carolina

Bank executive at the time. “Jim knew he'd

be recognized if people saw him at the

commission,” says Gaeta. “The whole

process can get pretty clandestine.”

The new banks vary

tremendously. Some, including High Street Banking

Co. in Asheville and Park Meridian Bank in

Charlotte, target doctors, lawyers and other

wealthy individuals. Others seek to serve average

people, including Scottish Bank of Charlotte

which resurrected a bank name famous in eastern

North Carolina from the 1930s through the 1960s.

Often, de novos spring

up after a local bank is bought by one of the

state's Big Four — Bank of America, First

Union, Wachovia or BB&T. A recent example is

American Community Bank in Monroe.

On a November day in

1998, Randy Helton glanced around the temporary

site of American Community and his eyes widened

in disbelief. Helton, president of the new bank,

had expected a few hundred investors and

customers to drop by for customer appreciation

day. Instead, 1,300 visitors poured in.

Helton had been

recruited only seven months earlier from First

Union Corp. by a group of Monroe business leaders

after First Charter Corp. of Concord bought Bank

of Union.

“The whole thing

was from the grassroots up,” says Helton.

“Until 1995, Union County had always had a

locally owned bank, and a small town like this

takes great pride in ownership. Suddenly, we had

eight regional banks like Bank of American, First

Union and Wachovia, and the smallest was First

Charter, a $2 billion bank.”

The banking commission

set American Community's minimum shareholder

investment at $6.5 million before opening. Helton

started selling stock in April 1998 and in 30

days found takers for one million shares at $11

each. The bank then offered another 300,000

shares. At the end of 90 days, it had raised

$13.7 million. Now, a little over year later, it

has assets of $57.5 million, is already

profitable, and will soon open its fifth branch.

Another spark for de

novos comes when banks reduce staff following a

merger. In that process some executives

invariable are left without jobs, creating a

restless talent pool. When Bank of Asheville

opened in 1997 its 11 staff members had 150 years

of experience. When Raleigh's Capital Bank, which

set a startup record by raising $27.5 million,

opened in June 1997, its president, James Beck,

already had nearly 25 years experience, including

having started the SouthTrust Bank franchise in

North Carolina. He and his top four executives

totaled 100 years in banking. Congleton had been

with BB&T for 17 years.

Jimmy Thomas, vice president for real estate

lending, chuckled at Cameron Coburn's question as

the two bumped into each other at the back door

of United Carolina Bank's Wilmington office one

evening three years ago. “Jimmy, have you

ever thought about forming your own bank?”

Coburn asked. “Where were you 10 years

ago?” Thomas replied.

Thomas and Coburn had

been offered positions with BB&T, which had

bought UCB, but both were evaluating their

options. So in June 1997 Thomas and Coburn found

themselves squinting at each other across a

single desk in a one-room office in Wilmington,

sharing a laptop computer and working the phones

for investors willing to commit $7.7 million.

“We thought we could do it overnight,”

says Thomas. “It took a year.” Bank of

Wilmington got its charter in June 1998, having

raised $9.3 million. Today, it has two offices,

including a second Wilmington branch opened in

August, and more than $40 million in assets.

Other success stories?

Catawba Valley Bankshares Inc., formed in Hickory

in 1995, today has offices there and in

Newton-Conover, with assets of nearly $112

million. And in Hendersonville, MountainBank,

chartered three years ago, has $108 million in

assets and four branches. Its third quarter

profits of $131,000 were up 285 percent from a

year earlier. That, notes president J.W. Davis,

“exceeded our net income for all of

1998.”

There is, of course,

more to the phenomenon of de novo banks in North

Carolina than hard work by motivated bankers.

History, regulation, luck and technology are on

their side, too.

“In Southern

business, real men start banks,” quips

Plath, the banking professor. “That's been

going on for three generations.” One theory

holds that the Civil War was as much an economic

as a social struggle. “The antebellum

attitude was that, to reclaim economic

independence, we had to become our own

financiers. We didn't want to have go hat-in-hand

to New York to ask the Yankees for money, and the

tradition of the merchant bank was formed.”

Visit Scottish Bank in

Charlotte. John Stedman Jr., founder and

president, spreads a scrapbook of yellowed news

clippings and advertisements on a table. They

date to the late 1930s when his grandfather, John

P. Stedman, founded the original Scottish Bank in

Lumberton. It was an era when banks gave toasters

and dinnerware to customers, and passed out dime

savings cards to encourage their kids to save.

First Union bought the

original Scottish Bank in 1964, but in 1972, John

Stedman Sr., John P. Stedman's son, formed

Republic Bank in Charlotte. Republic was bought

out by CCB Financial Corp. for $125 million in

1986.

Today, John Stedman Jr.,

who occasionally dons kilt and sword to promote

the latest Scottish Bank, chartered in 1998, says

he hopes to recapture the spirit of the original,

focusing on accounts for seniors, families and

small businesses. “Essentially all community

banks make a case that small businesses are

underserved, and that they can do better,”

says Harry Davis, professor of finance at

Appalachian State University and economist for

the banking association. Congleton, for example,

says the focus of Millennia Bank will be

enterprises of less than $1 million a year in

sales. Bank of Asheville, in only its second

year, has become the state's 14th largest

small-business lender, and has been named by a

local consumer group the minority-business lender

of the year.

North Carolina bank laws and regulatory

environment get credit, too. Capital Bank's Beck,

in Raleigh, notes that Depression Era statutes

that permitted development of branch networks set

the stage for community banks like Scottish Bank,

and that today's banking commission, under

Lingerfelt, plays a unique role. It's both tutor

and tormentor.

Throughout months

leading up to a charter hearing, the staff, say

de novo bankers, is nurturing and coaching.

“They're customer friendly,” in Plath's

words. That includes passing out a thick packet

of information, developed with the N.C. Bankers

Association, that presents a paint-by-numbers

approach to startups.

Then the charter hearing

becomes the final exam, a stern reality check.

“Up to that point, you've been out in the

community selling air,” says Sturges.

“`We don't have a bank, and we don't have a

charter, but, boy, it's going to be great!' Then

you go before the commission and think, `I've got

a year of my life and a million dollars of my

friends' and associates' money at stake. If I

don't do this right, I won't get a second

chance.'”

In addition to staff

help in preparing for the hearings, startup

bankers have available to them lots of expert

legal advice. In addition to Gaeta, the Raleigh

law firms of Sanford Holshouser and Moore &

Van Allen, along with Ward and Smith, of New

Bern, and in Greensboro, lawyer Ed Winslow of the

firm of Brooks Pierce, all focus on startups.

Winslow is also counsel for the Bankers

Association.

But in practice, the

tough regulatory environment has paid off.

Although two new banks, Crown National in

Charlotte and Bank of New Hanover in Wilmington,

failed when caught in the early-1990s recession

— they were insured and no depositors lost

money — others have generally prospered.

“Another big reason

for the explosion of startups this decade is that

we've not had a recession since 1992,” notes

Davis. “In February, this will become the

longest post-World War II recovery period, so it

has simply been a good time to start a

bank.”

One of the biggest

boosters, however, of de novo banks is

technology, simultaneously helping to create a

market for them but also giving them tools to

compete with giant rivals.

At the sprawling First

Union customer service center in suburban

Charlotte, a computer system called

“Einstein” helps customer service

representatives sort 45 million calls a year by

assigning each customer a small, green, yellow or

red square on the computer screen. That signals

to the representative the customer's minimum

balance and how profitable he or she is for the

bank. And that sets the tone for how the customer

is handled.

The bank saves $100

million a year by weeding out unprofitable

customers, such as those who call often to check

on their balance. But many customers like

personal service, and are the bread and butter of

community banks. “We don't compete with big

banks,” says Montgomery. “We complement

them.”

Other de novo bankers

think so, too. “Technology enables large

banks to focus on profitability instead of

personal relationships,” says Congleton.

“The majority of customers in an area like

ours, which is more rural and farm oriented,

still enjoy a bank that's willing to deal with

them on their turf and their terms.”

Technology also helps

keep equipment costs low. “We used to spend

millions of dollars for those big, blue

boxes,” says Sturges, a former CCB

executive, referring to giant computer systems

such as the IBM AS400, the $190,000 computer that

once was a mainstay of banking. Now, a $5,000

personal computer-based system can do as much.

“You no longer have a huge investment in

fixed assets,” adds Sturges. “In our

first year, we budgeted only $450,000 for

premises, equipment, the works.”

Banks also pare startup

costs by relying on a huge support industry that

handles everything from monthly statements to

credit and debit card servicing, all on an

outsourced basis. That helps minimize staffing.

Thomas, for example, notes that his bank, less

than two years old, offers both kinds of cards,

all possible deposit and loan services, ATMs, a

brokerage, and soon, electronic banking.

Outsourcing also puts

investor dollars to work. “Ninety-eight

percent of our assets are earning money, instead

of buying buildings or equipment,” says

Helton at American Community in Monroe.

“Technology levels the playing field with

the big guys. There's nothing they can bring to a

customer that we can't bring more efficiently and

more user-friendly.”

It's ironic that many

little banks tend to become big banks. Triangle

Bancorp of Raleigh mushroomed in a decade from

$53 million in assets to $2.3 billion before

being acquired by Centura Banks of Rocky Mount in

1999. As community banks mature, the very

investors who made them possible often want to

cash in when lucrative buyout offers come along.

“Founders put their hearts, souls and

pocketbooks into them,” says Woodard.

“But shareholders pressure them to sell, and

it's not often the gnat can swallow the

elephant.”

Not all go that route,

though. A few months ago, banners and flags flew

on the town square, as thousands turned out to

celebrate the 125th anniversary of First National

Bank of Shelby. “The one thing the big banks

haven't figured how to do yet,” says Plath,

“is to grow old along with you.”

COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL. This article

first appeared in the January 2000 issue of North

Carolina Magazine.

|