Hotel

Industry

The

Boom in Rooms The

Boom in Rooms

Growing market demand and favorable financing are behind

the continuing boom in hotel construction

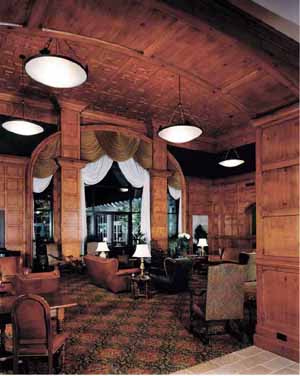

Below: The lobby of the O'Henry Hotel in

Greensboro. At right, the Sheraton Grand New Bern

received a $2 million renovation to take advantage of a

new convention center next door on the waterfront.

By Sandra L. Wimbish By Sandra L. Wimbish

You don't have to

look far to see the boom in the hotel industry because

new hotels are springing up like mushrooms across North

Carolina. Just in the past four years the number of hotel

rooms in the state jumped by more than 19,000, to

125,000, and the growth in some metro areas is stunning.

In Wake County, there now are 66 percent more rooms than

in 1996.

Wake's boom in hotels is due largely to its expanding

convention center business and state government

functions. The convention center trade also is spurring

hotel construction in Charlotte, where a public/private

partnership will soon break ground on a 700-room,

four-star Westin Hotel and a 1,650-space parking deck

across from the Charlotte Convention Center.

It's not conventioneers, but vacationers, that are

clamoring for more hotel rooms in other parts of the

state. Along the coast, in the Sandhills and the

mountains, leisure travelers are filling up a lot of new

rooms.

“There is very strong tourism in this state,”

says Bob Winston, the founder and CEO of Raleigh-based

Winston Hotels, which owns and operates 50 properties

nationwide, including 16 in North Carolina. “Couple

that with the fact that the state is in very good

economic health, and it spurns growth.”

New hotels create many new jobs. Industry employment in

North Carolina was 34,240 in 1996, according to

Employment Security Commission data. But at a better-than

2 percent annual growth rate, the number of hotel jobs

should grow to 41,910 within six years. In Guilford

County, 13,600 people are employed in travel-related jobs

and the county pulled in $752 million in 1998 in travel

and tourism revenue.

Favorable financing is facilitating the hotel boom. Until

October 1998, hotel financing was fueled mainly by

mortgage conduit financing on Wall Street. “And then

in 1998, the mortgage-backed securities for hotels

basically hit the wall,” says Doyle Parrish,

president of Summit Hospitality in Raleigh. “A lot

of those mortgage-backed securities were priced by the

Treasury bill, and the T-bill was at record lows.

Financing opportunities within the Wall Street markets

were plentiful.”

Financing was the lowest it's been in the past 20 or 30

years. Hotel loans were being put in place for a lot less

than 8 percent; sometimes as low as 7 percent. “In

our business,” Parrish adds, “it's very unusual

to see that kind of rate, one that is so close to office

building rates or commercial development rates. It's just

been a good economic environment for us.”

Combine the good rates with increasing consumer demand,

and you have the perfect combination for industry growth.

There are some in the industry who say the growth has

been too fast and uneven, pointing out that most of the

new hotels in the state are in the economy category

— Hampton Inn, for example. Of the 19,000 new hotel

rooms built in North Carolina in the past four years,

only 1,200 of them are at full service hotels offering

restaurants and meeting facilities.

Why so many new budget hotels? Because they make money.

“Most of the construction of limited service hotels

has been moderately to very successful,” says Hobbs.

One big reason so few full service hotels are being

built, despite the availability of cheap money, is that

they are just so expensive. “It's much more

difficult to finance full service hotels because they

require more equity from the ownership's side. In the

'80s and '90s we saw a lot of developers going for

selected serve. They understood that market, there was a

need for rooms, supply was not that prevalent in certain

areas, so they built selected serve,” says Parrish

of Summit Hospitality, which manages 10 properties in the

Charlotte, Wilmington, and Triangle markets.

Estimates range on a per-room basis anywhere for twice to

three times as much to build a full service property as a

selected service property. A limited service property

that costs on average $70,000 per room to build in a

metro market — excluding land costs — would

cost upwards of $150,000 per room as a full service

hotel. Additionally, says Parrish, “ a lot of full

service properties had horrendous problems during the

late '80s and early '90s when the (Resolution Trust

Corporation) owned a lot of them — and the lenders

have not forgotten that.”

Even when capital is not a challenge, there can be other

barriers that prohibit the successful execution of a full

service hotel. Getting a particular brand may become an

obstacle, as may the problem of simply not having the

expertise to manage such a large project.

When a developer finally does step up to the plate and

build a full service property, there appears to be

sufficient traffic to generate revenue. Summit

Hospitality says that in the markets it serves, the

Marriotts and Embassy Suites are doing well, and even

turning away business a couple of nights each week.

Winston Hotels, meanwhile, has tailored its recent growth

around mid-level hotels such as Hilton Garden Inn,

Courtyard by Marriott, Residence Inn by Marriott and

Homewood Suites. In the past five years, Winston Hotels

has built four properties in North Carolina — two

Homewood Suites in Raleigh, and a Courtyard by Marriott

in both Winston-Salem and Wilmington.

“We think that they capture the largest demographics

of the whole industry,” says Winston. “They

have the greatest overall appeal.”

How Hotels Capture Markets

The hotel industry is different from many other

businesses in at least one important way: Hotels only

“capture” the business that surrounds them.

“Only in the most extreme circumstances does a

property create demand,” Hobbs says. So when

businesses move, hotels start packing; and wherever

business parks are built, hotels are sure to follow

— even if there are fine properties located just

minutes away.

“When a community's economic center shifts away from

where it has been located, you'll see people come in and

build new hotels,” says Hobbs. “So the

properties that were built in the '70s and '80s, and even

more recently, will find themselves no longer the most

convenient property to this new center. Someone goes in

and builds a new property and then gets all the

business.”

It's a cold, hard truth. Regardless of its quality and

nearby location, a property can feel the squeeze when it

is no longer the closest one to the economic center. And

no longer being the new kid on the block doesn't help

either.

“There's been tremendous new hotel construction in

Research Triangle Park, and it's been able to capture the

business from RTP and western Wake County,” says

Hobbs. “It's been dramatic. There's not been that

kind of development in other areas of Wake County. Demand

has gone up — the total number of rooms sold grows

each year. But demand has not grown at the same level as

construction within the same time period. So it's not

like you build a new hotel and there are new people to

fill them up. What you see is a shift of properties that

were running at 70 percent occupancy in the mid-1990s are

perhaps now running at 60 percent or even somewhere just

above 50 percent occupancy. Again, you've got a lot more

rooms dividing up a growing amount of business, but it's

not growing at the same rate as we've had construction in

Wake County.”

When new hotels spring up, older ones are forced to trim

expenses. They may change brands; they may become

independently owned; they most certainly will lower their

rates and reduce amenities. But do they go out of

business? Typically not, says Hobbs. “The bottom

line is the property is no longer in the destination

— the location — that can generate the kinds of

revenue that can pay for upgrades and keeping the

property well maintained. An older hotel is not going to

make the money because it can't get the rates that the

new property can get because it's newer and more

convenient,” he adds.

The Convention Center Strategy

One bankable strategy for making yourself convenient,

if Lady Luck shines on your location, is to build a

convention center. Convention centers have been sprouting

up all along the mid-Atlantic region, including new

facilities in Washington, Charlotte and Baltimore. But

recently, smaller markets have become interested in

tapping into the revenue possible through the convention

business. While a convention center's operating costs

nearly always exceed its revenue, the traffic it brings

to local hotels, restaurants and other commercial

interests makes it profitable over the long haul.

New Bern, for example, has taken the plunge. Craven

County purchased a parcel of land in the late 1990s with

the intention of building a convention center. The city

seemed a natural for further economic development. New

Bern, founded in 1710, is the historic home of Tryon

Palace, the residence of British Royal Governor William

Tryon. It's also the birthplace of Pepsi, and boasts a

picturesque location on the river front.

Ground was broken in September 1999 for the Riverfront

Convention Center, with Virtexco as general contractor.

The design was based on a feasibility study conducted

five years earlier with funding from the Craven County

Tourism Development Authority.

“The study results suggested that we build a small,

high-tech center for a customer base that would include

association groups and corporate groups from within North

Carolina,” says Nancy Richardson, director of the

center, which is funded largely by revenues generated

from occupancy taxes. “We've booked some regional

business that is from South Carolina and West Virginia,

but we are not a first-tier or second-tier destination.

We don't have the infrastructure for national meetings .

. . although one day we will.”

Moving to capitalize on the influx of visitors the

convention center will bring, the neighboring Sheraton

Grand New Bern launched a $2 million renovation. Sonjay

Mundra, president and CEO of First American Hotels, and

Dicky Walia, chairman of the board of Welcome Hotels

Inc., acquired the hotel in January 1999. “We

basically gutted all the rooms and made everything brand

new in the building,” says Mundra.

To make itself stand out in the market, the New Bern

convention center will offer state-of-the-art technology.

It's being wired with more than 40,000 feet of data

cable, 38,000 feet of voice cable, fiber optic cable with

Category 5 telephone cable, and complete teleconferencing

and video-conferencing capabilities.

Farther down the coast, Brunswick County is enjoying a

boom in business fueled by golf. The Sea Trail Golf

Resort & Conference Center, covering 2,000 acres of

coastal property in Sunset Beach, has greatly expanded

its conference space to accommodate the surging number of

groups that want business meetings built around golf.

According to Marketing Director Nancy Foster, “the

demand for our conference facilities was outpacing our

ability to meet it. Because of our meeting space

limitations, we turned away groups who had been coming

here for years, but they had just gotten too big. At our

maximum we could not handle groups of more than 300

people.”

So Sea Trail added 30,000 square feet of meeting space.

The Carolina Conference Center opened for business in

December 1999 and received its final cosmetic touches in

April. All told, Sea Trail is now the largest conference

facility on the North Carolina coast, and can handle in

the vicinity of 2,000 people.

To make it easier for tourists, North Carolina is about

to enhance its web site so computer users browsing travel

and tourism information can go ahead an make room

reservations. The service, available at

http://visitnc.com, covers at least 240 hotel, motel and

resort properties.

Wish You Were Here

Economy hotels may dominate the market in numbers,

but properties at the top end of the scale also seem to

be doing well and are confident enough in their business

to wager major new investments.

The Grove Park Inn in Asheville knows that its upscale

clientele wants more amenities, so it's building a $36.5

million spa of world-class proportions. But Grove Park

doesn't want anything to block the scenic mountain vista,

so it's constructing a 40,000-square-foot, lavishly

designed facility underground, set below the inn's Sunset

Terrace. In addition to pools, saunas and steam rooms,

the Grove Park spa will offer treatments from massage and

aromatherapy to body scrubs, herbal wraps and mud wraps.

Pinehurst, too, has announced plans to develop a spa and

golf fitness center. The grand opening is slated for late

2001, with the expectation that guests will enjoy a more

complete resort experience. Because golf is the raison

d'etre at Pinehurst, there will be special golf fitness

features, with cardio, toning, strengthening and

stretching equipment, as well as treatment specifically

geared toward developing the body and mind of the

successful player.

Another segment of the full service hotel market is

addressing the same trend, but with a different twist.

The boutique hotel movement first took hold in cities

like New York and San Francisco, where there was a niche

for smaller hotels, unique in decor, that were part of

specific communities. The rooms were typically smaller

than those of larger, full service properties (at least

in primary markets), but they offered an appealing

ambiance to guests who wanted a community experience

while traveling. The O. Henry Hotel in Greensboro and The

Sienna in Chapel Hill are two boutique hotels that have

craftily carved out a piece of the hotel industry pie.

“When people travel today, they want to be taken

care of,” says Nancy King Quaintance, vice president

of Quaintance-Weaver Restaurants & Hotels Inc., which

opened the O. Henry in Greensboro last year. “The

length of stay for the leisure traveler is much shorter

today. Instead of taking a two-week vacation, people will

take a one-week vacation and a few weekend trips here and

there. But they want more pampering during that shorter

time. Likewise, business travelers who spend a lot of

time on the road want to be taken care of, too. If they

have to be away from home, they want to be someplace that

is at least as comfortable as home.”

To make certain that the O. Henry (named after the author

and Greensboro's native son) met its guests' high

standards, the hotel conducted focus groups to find out

just what amenities travelers wanted. “We found that

our customers wanted windows that opened. So when we

designed the hotel, we decided to use good old-fashioned

double-hung windows that can be opened for fresh

air,” says Quaintance. Once Quaintance-Weaver had

the laundry list of dos and don'ts nailed down, it built

a model room in a downtown warehouse and invited comments

from its client base. After the kinks were addressed, the

131-room hotel was built near Friendly Shopping Center in

Starmount, one of Greensboro's oldest neighborhoods.

Amenities like triple-sheeted beds, in-room microwaves,

afternoon tea and cocktails in the lobby, and dry

cleaning service make the O. Henry special, as do the

nine-foot ceilings, but the greatest boon is its

community setting, which is even convenient to Wendover

Avenue and Benjamin Parkway, two of Greensboro's most

traveled thoroughfares.

Chapel Hill's Sienna Hotel bills itself as a

European-style luxury hotel, and indeed its Four-Diamond

rating suggests it carries it off with panache. Like

other boutiques, the Sienna banks on offering the highest

level of personalized customer service. The decor was

inspired by the art, architecture and ambiance of Italy,

much like a Tuscan villa, and each of the 80 guest rooms

is individually appointed. The Sienna is just a 15-minute

drive from Raleigh-Durham International Airport, making

it a choice location for business meetings.

Return to magazine index

COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL. This article first appeared

in the June 2000 issue of the North Carolina mgazine.

|