|

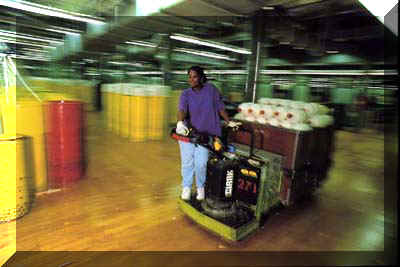

Patricia Hayes navigates a roving hauler in the link spinning area at

Cone Mills White Oak plant.

Photo by Roger W. Winstead

Smooth Move

A

helping hand proves better than a regulatory fist

in getting the kinks out of workplace ergonomics problems

Top tips for avoiding ergonomics injuries

By Lawrence Bivens

Talk to Anita Goehringer about her work, and it’s hard not to sit up

straight and keep your feet flat on the floor. Not that there’s

anything intimidating about her or the job that she has, but as

director of the North Carolina Ergonomics Resource Center (ERC),

Goehringer knows firsthand that seemingly minor aspects about how we

live and work can potentially affect our health and productivity over

time.

“Ergonomics is far more than simply a workplace issue,” Goehringer

explains. “Our bodies don’t stop working when we go home for the

day.”

But because most of us spend more of our waking hours working than any

other activity, job-related illnesses and injuries are a major concern

to employers across all industries because the costs are so

significant. In 1994, the latest year that data is available, the

average workers’ compensation insurance claim for carpal tunnel

syndrome, for example, was $14,280 once medical expenses and

compensation costs are calculated. For back injuries, the figure was

$16,881.

Building safer and healthier work environments can dramatically reduce

such costs. But there are even greater potential benefits, Goehringer

says. Productivity increases. Sick days are taken less frequently.

Employee turnover drops. Morale improves. “It’s a smart business

decision,” she says. “Being proactive with ergonomics can help

companies achieve larger business goals.”

Help Is On The Way

Goehringer has seen it happen. The center, founded in 1994 as a

partnership between the state Department of Labor and N.C. State

University, has worked with dozens of firms large and small in

overcoming workplace health and safety hazards, some very serious.

Hundreds more have benefited from the center’s research, information

and educational programs.

“People have come to us from all over the country for help,” she

says, “though we have an obligation to serve those inside North

Carolina first.”

The center works directly — and confidentially — with employers in

identifying, analyzing and correcting ergonomic deficiencies in the

workplace. Its expertise extends across both manufacturing and office

environments. In return, companies pay a professional service fee to

the center, which also acts as a membership organization and earns

part of its budget from the dues it collects from member firms.

There are three levels of membership through which employers can

participate in center programs. “Practicing Members” are those

organizations currently implementing or maintaining ergonomics

programs within their facilities. Annual dues of $100 allow them to

utilize all the center’s services on an “as-need” basis.

Associate Members ($250) include consultants, practitioners, trade

associations, vendors and others providing ergonomics-related products

and services.

“Developing members — they’re the ones who really make the

center unique,” Goehringer says. These employers participate in a

comprehensive, three-year ergonomics program that is developed and

implemented for their worksite. The custom tailored ergonomics program

is designed specifically to control the development of musculo-skeletal

disorders, and dues are based on the facility’s size, the nature of

the work involved and number of employees. It is through this

relationship with the center that employers in North Carolina have the

opportunity to demonstrate that they are complying with state

regulations that call for evaluating the prevalence of

ergonomic-related concerns in the workplaces and for taking

appropriate remedial action.

With its ties to N.C. State — it is considered a unit of the College

of Engineering — the center emphasizes applied research. Its staff

is drawn from a patchwork of disciplines, including occupational

therapy, kinesiology, industrial engineering, allied health and other

fields. Since its founding, the center’s primary goal is

facilitating technology transfer and information exchange between the

university, state agencies and industry.

“The center was the brainchild of several different people at the

university and at the Labor Department who were concerned about the

high rate of cumulative trauma disorders in North Carolina vis-à-vis

the rest of the U.S.,” according to Goehringer. Today, the

center’s membership totals 250, and its staff of 10 is drawn from

all over. The number includes faculty, students and interns from

universities around the region and others from the private sector.

“We’re not typical of either a university setting or a government

agency,” she says.

“Their association with N.C. State brings a lot of added value,”

says Frank Cruice, corporate safety manager for Perdue Farms Inc. The

Maryland-based poultry giant maintains extensive operations at eight

sites around North Carolina, employing an estimated 4,500 in the

state. After an OSHA citation in the late 1980s, the company embarked

upon an aggressive ergonomics program that is now held up by

government regulators as a model program.

“With the help of ERC, we conducted ergonomics assessments at our

facilities both inside and outside North Carolina,” Cruice says. The

resulting program led to an exhaustive series of job task analyses,

the creation of ergonomics committees at each site that includes

management, safety personnel and line workers, new training programs

for all levels of personnel, the establishment of wellness centers at

most locations and numerous other measures. As a result, the firm’s

workers’ comp premiums have dropped by 70 percent, and its claims

history is now the lowest in the poultry industry.

Firms in other industries can also attest to the center’s value.

“The ERC is a huge asset for the state of North Carolina,” says

Ken Blake, manager of safety, security and industrial hygiene programs

for Cone Mills Corp. in Greensboro. “They’re right on the cutting

edge of all this.”

The company, the world’s largest maker of denim, employs a workforce

of more than 4,000 at seven manufacturing sites in North and South

Carolina. Its interest in ergonomics began in the 1980s, but it found

information resources on the issue scarce. In 1991, Blake began

writing his own ergonomics manual for the company. The company’s

motivation was simple: survival. “We realized then that our future

human resources were going to become scarce. Something had to be done

to minimize injuries to our people if we were going to remain

competitive.”

Several years later, the company hooked up with the ERC, which helped

with the job analyses, the starting point of most ergonomics programs.

It identifies the risk factors, known as “stressors,” associated

with any given activity. “We found our biggest risk factors were in

our materials handling and in the lifting of heavy rolls of yarn,”

Blake recalls. Once the risk factors were singled out, Cone Mills’

officials and ERC consultants focused on improving the methods used by

employees in doing these jobs. Solutions were surprisingly simple and

involved little disruption. One lifting task, for example, was

previously performed with employees “pinching” the object with the

fingers of one hand, a practice that isolated a high degree of strain

on a relatively small muscle group. The new process calls on workers

to make full use of both hands, a far healthier alternative.

“In most cases, the solution is much less expensive than a single

injury would be,” Blake says.

Cone also collaborated with the center in the design of educational

materials. “One of the key elements you’ll find in our ergonomics

program is education,” Blake says. Cone’s training program

emphasizes the factors that lead to the most common injuries — both

on and off the job. Recreational and fitness activities such as

bowling or weightlifting frequently place people at high risk of

certain types of injuries. “It’s not unusual that one of our

nurses finds an ergonomic problem that was created at home,” he

says.

Cone’s results have been impressive. Since 1991, incidences of

back-related injuries have declined by 90 percent. Simple strain

injuries have been reduced by 85 percent. In fact, the company has

watched its overall injury rate decline in each of the past five

years. “Of course, our workers’ comp premiums have also

declined,” Blake says.

Safer Jobs, Lower Rates

Statewide, recent years have seen a steep decline in workers’ comp

costs, and North Carolina currently boasts the eighth-lowest rates in

the country. To many, that’s solid evidence that employers are

taking the necessary steps towards improved workplace safety and

health without additional regulations from state and federal

government.

“My feeling is that North Carolina employers realize how important

their workers are,” explains Cherie Berry, state commissioner of

labor, “and they’re out there correcting problems voluntarily

because it makes good business sense.”

Recent months have seen a flurry of legislative and regulatory

activity surrounding the prospects of a uniform set of national

ergonomic standards that all workplaces would be expected to meet. In

early March, Congress overturned the federal ergonomics rules that

were issued only a few months earlier, with President Bush signing the

repeal shortly thereafter. At the same time, Berry took similar action

to delete state level rules.

An array of business and other organizations, including NCCBI,

actively opposed government mandated ergonomic standards on either

level. Part of that objection is based on the absence of conclusive

scientific research and the lack of definitive diagnostics that link

certain injuries to on-the-job activities.

“Because of the ambiguity of the research that’s available, no one

could agree upon a standard,” says Leslie Bevacqua, NCCBI’s vice

president of governmental affairs. Even physicians were skeptical

about the validity of the data on the causes of workplace injuries.

Carpal tunnel syndrome, for example, though frequently brought on by

repetitive motion tasks, is also caused by thyroid disorders,

diabetes, menopause, kidney disorders and numerous other medical

conditions. Others opposed to uniform standards cite the need for

flexibility in addressing unique workplace needs.

“I’m a strong proponent of businesses being able to develop their

own programs to fit their needs,” says Blake of Cone Mills. “These

issues don’t lend themselves to a one-size-fits-all approach.”

Even more alarming was the new regulations’ redundancy: “Under

existing North Carolina law,” Bevacqua says, “employers must

maintain safe workplaces for all their workers. If they see any type

of hazard, they are required to eliminate it, and it’s clear that

they do this already.”

Commissioner Berry believes the answer to ergonomics problems in the

workplace can and are being resolved through better education — for

both employers and employees — on the steps needed to build

healthier work environments. The noisy controversy over federal and

state standards has served a useful purpose as a “wake-up call” to

people who may not have known that problems exist.

One resource Berry recommends for employers is the Labor

Department’s Bureau of Consultative Services. The free service

supports both business and government entities in achieving safer,

more healthful workplace. The bureau deploys its own team of

experienced safety specialists, industrial hygienists and ergonomics

consultants to assist employers in identifying safety and health

hazards and offer advice on reducing and eliminating them. They are

also available to assess an organization’s workplace safety and

health programs. The goal is to help employers meet existing OSHA

regulations.

“I would encourage any employer to contact the bureau,” Berry

says. “It’s one of the most business-friendly things we do.”

Bureau consultants provide clients with a comprehensive written report

containing their findings and recommendations. The employer’s

obligation in accepting these services is to correct all hazards

identified by the consultant within a reasonable time period. Other

services include technical assistance, sample programs, air sampling

and analysis, and noise measurements. All services are confidential

between the employer and the bureau, which is forbidden to share

assessment results with its regulatory counterparts.

Services are provided by a staff of 18 consultants and are typically

oriented toward corporations with no more than 500 workers. Municipal,

county and state government agencies of all sizes may also take

advantage of the programs.

The center and the Labor Department share training resources and

expertise. Labor provides OSHA technical support and advice for the

center’s Office Ergonomics Accreditation Program, a comprehensive

curriculum that builds in-house ergonomics expertise. In turn, ERC

shares its latest findings on the applied research front with Labor

Department officials in North Carolina and elsewhere.

“Ours is really a one of a kind

program in the nation,” Goehringer says, “and we’re frequently

asked by other states to help them design something similar.”

Ergonomics Tips

Adjust your chair to fit your

body. Adjust the height to keep your arms down by your side and

shoulders comfortable while working.

If necessary, use a footrest or box to support your legs and

feet. Adjust the

chair’s backrest to support your lower back.

Adjust your chair to fit your

body. Adjust the height to keep your arms down by your side and

shoulders comfortable while working.

If necessary, use a footrest or box to support your legs and

feet. Adjust the

chair’s backrest to support your lower back.

|