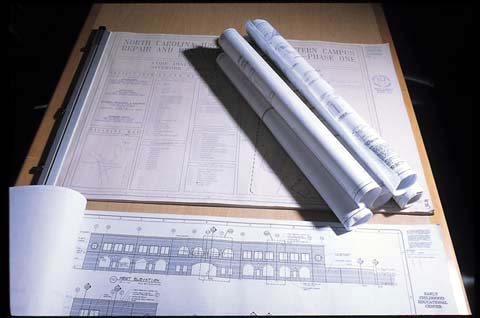

Designing the

Future

A bond money-fueled boom in

campus buildings

begins changing the face of higher education

By Lawrence Bivens

Most

around the country remember Nov. 8, 2000, as the day of the closest

presidential vote in U.S. history. But for many in North Carolina the

same date marks a far more decisive victory. That was when Tar Heel

voters overwhelmingly approved a $3.1 billion bond referendum in

support of the state’s public universities and community colleges.

“While the passage of the bond measure meant a lot to us (college

presidents) financially, it meant even more emotionally and

psychologically,” says John Dempsey, president of Sandhills

Community College in Pinehurst. “It said to us that our communities

overwhelmingly support the work we’re doing.”

For most students at Sandhills, one of the state’s 59 community

colleges, approval of the bond package will mean more and better space

in which to learn. For the 40 or so enrolled in the Sandhills’

culinary arts program, it was needed in order to have any space at

all. “Right now, our culinary students have to run around to

kitchens of various restaurants around the county in order to get

their work done,” Dempsey explains. But plans are under way to

construct a new building at Sandhills that will be home to the

college’s culinary students, as well as its technology programs.

More than $3.8 million of the building’s estimated $6 million will

come from state bond funds.

In all, Sandhills Community College is set to receive a total of

nearly $13.6 million. Atop Dempsey’s wish list for the funds is a

second building for the college’s Hoke Center. In additional to

serving Moore County, Sandhills’ presence in neighboring Hoke County

is growing. The college’s 300 students there are currently taught in

a downtown Raeford office building, although the first building at its

Hoke Center, financed separately, is set to open this month.

But more is needed. “Because Hoke County is growing and our programs

are growing, we’re going to need a second building there and

potentially even a third,” Dempsey says. The second building, which

will be known as the Hoke Business and Technology Center, will house

new programs the college is not currently able to offer in the county.

Among them, Dempsey says, is economic and workforce development

programs that the county, among the state’s most rural, critically

needs. The estimated price tag for the center is $1,788,125, about

half of which will come from bond funds.

“When industrial clients consider our county as a potential

relocation destination, the first thing they want to know is, Is there

qualified labor?” says Don Porter, executive director of Raeford/Hoke

Economic Development. “In the past, we could only talk about what a

tremendous asset Sandhills Community College would be for them — or

drive them over to Pinehurst. Soon, we’ll be able to point to

state-of-the-art training facilities and say, ‘These are the

resources that will support you here.’ ”

Meeting a New

Mission

In other corners of the state, bond monies are helping community

colleges cope with the physical side of new and changing demands they

must respond to. At Brunswick Community College in Supply, campus

leaders view $1.4 million worth of renovations and additions to their

Technical Trades Building as a way to address both space and

curricular challenges. In this case, nearly $473,000 in funds received

from the county’s board of commissioners got the project out to the

starting gates. The remainder will come from the bond issue.

Recent years have witnessed rapid changes in the county’s population

and economy, two trends Brunswick Community College must keep pace

with. Once a sparsely populated land with an economy based on

agriculture and tourism, Brunswick County is now a leader in growth.

The surge in its population — during the 1990s, it grew a whopping

43.5 percent, according to U.S. Census figures — has mainly been

concentrated among the ranks of retirees, a fact that has placed

intense pressures on the local homebuilding industry. Those demands

have spilled over to the college, which is doing its best to produce

enough skilled construction workers.

“We’ve been working with the local homebuilders associations on

satisfying their labor needs,” says Michael Reaves, president of

Brunswick Community College. “The high schools here maintain a

construction training program, but lacked adequate facilities.” With

builders calling for more advanced skills, the college has partnered

with the school system in offering a building trades program that will

be run out of the upgraded facility.

And there have been other curricula added to the offerings at

Brunswick Community College — made possible by the more

accommodating digs that are on the way.

“The building was designed at a time when most of our students were

learning auto mechanics, HVAC and electronics,” says Johnnie

Simpson, vice president for instruction at the college. “Today,

it’s programs like computer engineering, aquaculture, industrial

maintenance and turf maintenance.” The latter program, she explains,

is increasingly central to the plethora of new golf courses springing

up around the region.

Leaders at Edgecombe Community College in Tarboro don’t need new

facilities for turf or carpentry programs, but they are just as

excited about what the bond funds will do for their campus and their

rural county. Site preparation work is currently under way in advance

of the college’s new Arts, Civic and Technology (ACT) facility. The

64,000-square-foot building will contain a technology center and

classroom space that will support the college’s programs in

networking technology, computer studies and industrial technology. The

multi-purpose space also will house a 1,200-seat performing arts

auditorium and a large reception area. The total cost of the project

is $10.5 million, though $3 million of that amount is being raised

from private donors.

“The $3 million is basically the cost of the auditorium and

reception areas,” says Charlie Harrell, vice president for

administration at the college. “We didn’t believe it was right for

the bond money to finance that portion of the building that wasn’t

strictly a part of our educational mission.”

Edgecombe Community College recently completed $250,000 in renovation

and repairs to the roof of its Vocational Shops Building, a project

that was financed completely from bond revenues. Constructed in 1971,

the facility houses the college’s mechanics and computer science

programs, as well as its day care center. “Serious leakage from the

roof kept us from making other improvements we needed inside,”

Harrell continues. “But now the students are loving it — and our

faculty even more so.”

The Medical

Biomolecular Research Building at UNC-Chapel Hill

is a nearly $65 million facility, of which $22.7 million will come

from state bonds

Desperate for Space

With $2.5 billion in bond proceeds earmarked for the state’s public

universities, those 16 campuses are also gearing up for major

improvements.

As of June 1, more than half of all projects in the universities bond

package were in some stage of completion, either advertising, design,

out for bid or construction. A similar status report of community

college projects isn’t available due to the large number of

institutions and the complexity of their local-match funding.

A major portion of the $46.3 million going to Elizabeth City State

University (ECSU) will be spent renovating campus residence halls,

which officials say are in desperate shape. “Approximately 50

percent of our students live in residence halls,” says Marsha

McLean, director of university relations and marketing at ECSU. But

the age of the campus dorm buildings averages 40 years old. “Only

three of our eight residence halls have air conditioning and just one

is wired for the Internet.”

Others require extensive plumbing and electrical upgrades. “Students

and parents have expressed concern when they see the inadequacies of

our residence halls,” McLean says. The resulting dissatisfaction and

negative word-of-mouth, she adds, have been enough to deter some

prospective students from enrolling at the institution.

Currently in design phase at ECSU are comprehensive renovation plans

for Mitchell-Lewis Hall, Wamack Hall and Doles Hall. Those projects

will total more than $7.2 million. And the campus also will spend $5.5

million on constructing a new residence hall. “Ultimately, we will

gain 200 dormitory beds that will help address our expected enrollment

growth over the next eight years,” says McLean.

McLean and others at ECSU also are looking forward to a new $8.8

million student center that will augment existing recreational

facilities and enable the university to consolidate its student

services into a single convenient location. “The new student center

is long overdue,” McLean says. “The current center was built in

1968 when ECSU’s enrollment was half of what it is today.”

An anticipated crush of new students over the coming decade is also

the basis for much of the planning at East Carolina University (ECU),

which is receiving $190.6 million in bond proceeds. About $55 million

of that amount is being put toward the completion of ECU’s new

Science and Technology Building.

“Right now, we’ve got students starting their lab work at 7 a.m.

and others working until 10 at night because we don’t have enough

lab space,” explains Phil Dixon, immediate past chairman of ECU’s

Board of Trustees. If left alone, the problem would only worsen.

“Our student body is projected to grow from 18,000 to 27,000 over

the coming decade.”

Set for completion by the fall of 2003, the Science and Technology

Building will be home to ECU’s chemistry department and its School

of Industry and Technology. Both are currently housed in the Flanagan

Building, a deteriorating structure built in the 1930s. “You simply

can’t teach sciences in the 21st Century with facilities that are so

antiquated,” Dixon says. With the approval of the bond package, ECU

is now set to grow substantially, especially in the health science

fields that have risen in popularity in recent years. “Allied health

has become such a big part of our programs.”

Other bond-funded projects at ECU include a new building that will

house the School of Nursing, the School of Allied Health Sciences and

a Developmental Evaluation Clinic. University trustees are expected to

select a site near the Brody School of Medicine later this year, with

construction beginning on the $46.9 million project by early 2003.

Watching from

the Web

In March, ground was broken for a new science building at UNC-Greensboro

(UNC-G), a project that has campus officials so delighted that

they’ve placed a web cam on the construction site. “You can log

onto our web site (www.uncg.edu)

from anywhere in the world and see the progress we’re making,”

Chancellor Patricia Sullivan says with a laugh. The

173,000-square-foot building, set for completion by the fall semester

of 2003, will be the largest on campus.

For Sullivan, the Science Building has been a top capital priority

since 1996, and the project will consume more of the school’s nearly

$160 million in bond money than any other. “The current building was

built as a WPA project in 1939,” Sullivan says, referring to the New

Deal program that was responsible for many of that era’s buildings.

“We’ve been sitting on a safety hazard.”

With a price tag of $47.7 million, the four-story structure will

contain research and instructional space for chemistry and

biochemistry. The biology department also will have classroom and

student lab facilities there. All told, an estimated 2,600 students

will participate in classes there annually.

Sullivan and others at UNC-G are particularly pleased with the design

of their new building. For faculty, an “open and invitational

ambiance” was key to incorporating a human element into the space.

Thus, an expansive atrium area, a lounge and a series of airy lobbies,

which are meant to facilitate informal conversation, are woven into

the building’s attractive design.

Safety and environmental concerns also are major themes for the new

building. “The No. 1 issue, especially for the chemistry labs, is

safety,” explains John Atkins, an architect and co-founder of the

Durham-based firm of O’Brien/Atkins Associates, which designed the

facility. “We wanted, for example, the labs designed in such a way

as to give instructors unobstructed visual supervision of all students

at all times.” Features such as ventilation were also critical.

“In the event something does go wrong, you don’t want fumes

collecting. We also wanted to make sure we were being sensitive to

environmental concerns and energy efficiency.”

Included in the new building will be state-of-the-art instructional

gear, an Internet connection for every two students at lab benches,

lab equipment feeding directly into computers, and modern audio and

visual equipment in labs, classrooms and lecture halls.

Long a leader in the use of campus computing, UNC-G is also poised to

benefit from the $4.1 million in bond funds set aside to upgrade its

aging technology infrastructure. “We were one of the first campuses

to go with fiber optics back in the 1980s,” Sullivan says. “Given

the way technology changes, the infrastructure we had was getting

old.”

Thus far, UNC-G has completed half its infrastructure upgrades. With

its networking hardware up to date, Sullivan sees the path clear for

the university to continue to develop innovative web-based programs

for students both on and off campus. “The new infrastructure will

certainly play an important role in delivering distance education,”

she says. But she points out the network also is key to the

reliability of new administrative computing systems that students,

faculty and administrators are increasingly counting on. “More and

more of our student services are going online, as are financial

management applications like purchasing and budgeting.”

Return to magazine index

|

|