Learn

more about Asheville: Learn

more about Asheville:

See 'Paris of the South" on

foot

Asheville stars in Hollywood

Business and travel information

on Asheville can be found at:

www.ashevillechamber.org

and www.exploreasheville.com

High Tech, High

Up

Asheville, long known for its

culture

and urbane flair, quietly emerges as

an information technology hotbed

By Lawrence Bivens

From

his computer workstation, Ian MacDonald gazes out an office window at

the Blue Ridge mountains. It is a panorama sparkling in a kaleidoscope

of red, yellow and orange leaves against a cloudless afternoon sky. So

idyllic is the view that MacDonald, a 32-year-old programmer at

Asheville’s e-Worker Technologies, struggles to conceal his

giddiness at having such working conditions. It is, after all, only

his first week at the company, having just moved from Atlanta, but his

expression belies a man who knows he made the right choice.

“My wife and I have always loved Asheville and talked about living

here,” the Fairfax, Va., native says, “but there just weren’t

that many of these types of companies here.”

Such is surely the sentiment of many who have visited Asheville, seen

its extraordinary quality of life and pondered making a home for

themselves here. Until recently, chasing such dreams likely would have

meant grappling with a labor market top heavy with low-tech, low-wage

jobs in heavy industry. But with the arrival of companies like

e-Worker, which designs and runs software agents for a diverse list of

clients, professional opportunities for the likes of MacDonald and

other urbane technophiles fleeing the Big City are becoming more

commonplace.

e-Worker announced the selection of Asheville as its headquarters back

in June. Moving from a site in nearby Brevard, the company quickly

leased office space and ramped up a youthful 15-person workforce with

an average wage than is more than twice that for Buncombe County

overall.

“We basically outgrew our space in Brevard and had to go

somewhere,” explains Rich Purcell, the company’s founder and CEO.

After considering Atlanta and Charlotte, Purcell chose Asheville

because of an interest he noticed its leaders had in growing software

ventures like his. “We were really impressed with the overall vision

this community has for attracting high tech firms,” he says.

It turns out that vision was not created by accident. Working

together, the Asheville Chamber of Commerce, the Buncombe County

Economic Development Commission and other community and business

leaders set out in 2000 to bring technology companies to Asheville,

which they see as just the sort of environment in which today’s

knowledge workers would love to live and work.

A Tradition of Creativity

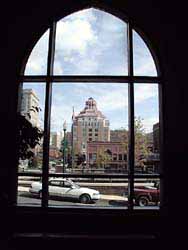

Left:

A view of Asheville City Hall Left:

A view of Asheville City Hall

Given Asheville’s pleasant climate, strong educational resources,

top-notch health services and easy access to key business destinations

such as Atlanta, Charlotte, Greenville-Spartanburg and Knoxville, one

would assume its appeal as a corporate outpost is self-evident. But

more was needed, and leaders systematically set out to highlight the

assets that could get the attention of technology industry executives

and entrepreneurs.

Since before the time of Thomas Wolfe, Asheville’s favorite son, the

city has tended to attract and inspire creative types: artists,

writers, designers, musicians. Thus, it seemed a natural fit for the

softer side of the Information Age — the multimedia content

providers who work with video, audio, animation, images and text using

the World Wide Web, CD-ROMs and DVDs as their delivery vehicles.

It is not a corner of the technology world that is void of economic

opportunity. The computer graphics industry, of which multimedia is

part, is expected to achieve annual revenues of $150 billion by 2005,

according to Machover Associates Corp., a White Plains, N.Y. research

firm that tracks the sector. The figure represents more than twice

what the industry earned in 1999, and economic impact models estimate

that for every multimedia job created, six more arise in related

fields to support it.

“We also learned that most companies in part of the technology

industry are niche oriented with 50 employees or less,” explains

Nancy Foltz, an Asheville marketing consultant who helped author the

city’s technology recruitment strategy. “That means they have a

fairly small footprint,” one that can easily be accommodated in a

community without a large supply of sprawling industry-ready land. It

also minimizes the adverse impact economic growth might have on the

area’s fabled quality of life.

Such a strategy also leverages the excellent educational resources at

Asheville-Buncombe Technical Community College, the numerous private

institutions nearby and those at the University of North Carolina at

Asheville (UNC-A). In 1998, for example, UNC-A unveiled a unique

program in multimedia arts and sciences, the only one of its kind in

the 16-campus UNC System. Students may concentrate their studies on

music, video, 3-D animation or interactive design, but all must

complete multi-disciplinary coursework that includes computer science,

mass communications, drama, art and music.

“As a liberal arts campus, you don’t tend to think of us as a

technology resource,” says UNC-A Chancellor Jim Mullen, “but we

are.” The school’s computer science program, he says, is highly

regarded nationally, with a faculty that routinely consults with

businesses in Asheville and around the United States.

Laying Down the Lines

Becoming a prime technology destination requires more than just access

to workers. Asheville leaders know that they will also need a

telecommunications infrastructure that can match those found in large

metropolitan areas. That is part of the vision behind 750-acre

Biltmore Park, the neatly planned community that blends office space,

housing, retail, education and more — all wired with the latest

fiber optics and networking hardware.

“There is a world class technology infrastructure here,” according

to e-Worker’s Purcell, whose firm consumes about 3,200 square feet

of space at the park.

Just like access to water, rail and power has long been a basic

criterion for arriving companies, being able to count on a speedy

Internet and strong digital voice connections is now seen as critical

to Asheville’s economic development efforts on all fronts.

“What we’ve done here is far more than real estate development,”

explains Jack Cecil, president of Biltmore Farms Inc., the century-old

company that controls the park. “It’s about putting together all

the pieces that make a community.”

Cecil’s strategy is not entirely original. It is, in fact, the

modern incarnation of what his great-grandfather, George Washington

Vanderbilt, strived for when he began erecting Biltmore Village in the

1890s — a sustainable community where diverse residents could live,

work, learn and play together. “The historical context was already

here,” Cecil says. “We’re just putting a 21st Century stamp on

it.”

Beside e-Worker Technologies, there are other tenants at the park,

including the North American headquarters for Volvo’s Construction

Equipment unit. In the late-1990s, the Sweden-based automaker moved

its offices from downtown after considering a move to other cities. It

now occupies 50,000 square feet at Biltmore Park.

For major employers in and around Asheville, there is a noticeable

European flair. Sonopress LLC, part of the Berlin-based media

conglomerate Bertelsmann AG, employs more than 1,000 workers at its

local production site. The 410,000-square-foot facility makes DVDs,

CDs and CD-ROMs. Earlier this year, Continental Teves, a German

manufacturer of automotive breaking systems, added 125 high-paying

jobs to its already significant Asheville workforce. Others, like

Chicago-based Bussman Industries and Ohio’s Eaton Cutler-Hammer,

have major manufacturing sites here that ship much of their product to

markets overseas.

At times, Asheville’s positioning as a technology outpost yields

dividends in its recruitment of industrial manufacturers. Such was the

case earlier this year when BorgWarner Turbo Systems selected the city

for a new corporate headquarters and technology center. The firm had

maintained a production site in Asheville since 1980. “The fact that

companies like Volvo and BorgWarner, which have had a presence in

Asheville previously, have brought additional operations here speaks

well about the quality of our workforce,” says Dave Porter, who

directs the Buncombe County EDC.

“The decisions by BorgWarner, Cutler-Hammer and others to locate

engineering and technical support centers here are very

encouraging,” says Gordon Myers, an executive with Asheville-based

Ingles Markets who chairs AdvantageWest, an economic development

partnership that represents 23 western counties, including Buncombe.

“The fact that many of these companies already had a presence in the

region says a lot about the quality of our workforce.”

In collaboration with others in the region, AdvantageWest has led the

way in researching the rapidly changing labor force needs of arriving

companies and those already here. The partnership also recently

launched an Internet-based resource directory, on the web at

www.workready.net, which will be especially valuable to small- and

mid-sized firms in minimizing the red-tape that comes with recruiting,

hiring, training and managing their workers. “The site further

demonstrates our region’s friendliness both to business and

technology,” says Myers, who currently chairs NCCBI and serves on a

list of statewide leadership roles.

Opportunities at Enka

Even when a prominent corporate name chooses to consolidate its

operations elsewhere, Asheville leaders turn the move into an

opportunity. That was certainly the case in the suburban Asheville

community of Enka, where BASF, the Swiss chemical giant, is shuttering

most of its local presence, a move that is expected to shower an

ironic array of benefits to the area.

The company, whose Southeast operations are being consolidated in

South Carolina, announced in October 2000 that as it vacated Asheville

it would deed over its leafy corporate campus to the local community

college. With 37 acres and 225,000 square feet of space, the move was

hailed by then-Gov. Jim Hunt as “the largest property donation in

history to any community college in the country.”

It was an offer officials at Asheville-Buncombe Technical Community

College couldn’t refuse, even though it meant they would have to

sink some major capital funds into bringing the 1960s-era buildings up

to modern safety and accessibility codes. With help from the state’s

higher education bond proceeds, A-B Tech has embarked upon an

ambitious plan to convert the site, originally home to American Enka

Corp. before it acquisition by BASF, into a small-business incubator,

corporate training and conference center, Cisco Systems Networking

Academy and more. All told, the campus is projected to generate $3

million in economic largesse annually, according to a study done by

the Asheville Area Chamber of Commerce.

“We plan to use much of the space there as a bio-technology

incubator,” says K. Ray Bailey, president of the college. Much of

the campus is tailor-made for such use. Among other activities BASF

conducted there were extensive research, development and testing, and

its abundant wet-lab space can readily support bio-tech innovation.

“About $1 million of the $14.1 million we’re getting from the bond

package will be going to Enka,” Bailey says. The new facilities will

offer welcome relief for A-B Tech’s crowded main campus, which

accommodates some 25,000 students enrolled in the school’s

curriculum and non-credit programs.

Bio-tech is another arena ripe with exciting economic development

opportunities for Asheville and surrounding communities. Given such

unique topographic, climatic and other geographic conditions, there is

a capacity to cultivate an enormously diverse array of plant life,

much of which can offer medicinal qualities.

“Our region has the second most diverse flora anywhere in the

world,” explains George Briggs, director of the North Carolina

Arboretum. A unit of the University of North Carolina General

Administration, the 15-year-old arboretum conducts research and offers

educational programs about the area’s vegetation and how its

commercial potential might be harnessed. “A-B Tech is already one of

our major partners,” continues Briggs, who is eager to see the

Enka’s bio-tech incubator move ahead.

Western Carolina University (WCU) and UNC-A also are joining in the

redevelopment of the Enka campus, with plans to offer programs and

courses that complement the center’s entrepreneurial mission.

“We’ve already begun discussion for the three of us (WCU, UNC-A

and A-B Tech) to collaborate on a bachelor’s degree program in

bio-technology,” says John Bardo, chancellor at WCU. His institution

already maintains a visible presence in Asheville, offering

undergraduate and master’s-level courses in business, public

administration and nursing.

“We’ve been in Asheville since 1937,” Bardo says of WCU, whose

main campus in Cullowhee is about an hour’s drive away.

Among the industries benefiting from the steady stream of allied

health graduates coming out of WCU and A-B Tech is the city’s huge

medical community.

“We get terrific support from WCU’s graduate nursing program,”

says Bob Burgin, CEO of Mission St. Joseph’s Hospital, “and

we’re blessed to have access to one of the best community colleges

in the state.”

The hospital has more than 500 physicians on staff, a testament not

only to the role it serves as a regional health center but also to the

fact that the city has become a sought-after posting for medical

professionals. “In most communities, physicians come and go,”

Burgin says. “But very few of those coming here ever want to

leave.”

The ubiquity of Mission St. Joseph’s — it is the largest North

Carolina employer west of Hickory — is symbolic of Asheville’s

rich history as a sort of Mecca for health and healing. Since its

earliest days, the city has been a destination for those needing

health services, be they from Western North Carolina or beyond. More

recently, the city and surrounding region have become a haven for

retiree migrants from around the nation. Though most coming to the

area are relatively youthful, healthy and engaged, Burgin points out

that there is an inevitably high demand for health services by those

over age 65.

Asheville’s burgeoning health care industry is also a factor in its

technology vision. It is an industry, Burgin and others point out,

increasingly reliant on advanced technologies. Thus the community

might make an attractive location for software development ventures

oriented toward applications in health care delivery.

“There is another hidden benefit there,” explains Nancy Foltz.

“Asheville’s doctors may also be a good source of investment

capital to drive some of those companies.” She adds that the

city’s leadership in the hospitality, outdoor recreation,

electronics and industrial equipment industries offers the same

potential for software design firms looking to cultivate markets in

those industry clusters.

Something for Everyone

Asheville’s population of both new arrivals and those who are proud

to be natives is a unique mixture of young hipsters, casual mid-career

adults and active retirees. It is one of the very few cities that can

boast of being named by Rolling Stone as “Amerca’s New Freak

Capital” at the same time Money was calling it “One of the Best

Places to Retire.” There is a one-of-a-kind mix here that some label

“Mayberry-meets-Berkeley.”

That vibe, local leaders contend, can only complement the city’s

efforts to grab the attention of the technology industry, which can

count on a multi-generational pool of Internet-bred worker bees,

seasoned managers and savvy elders who’ve watched many a business

fad come and go.

The third plank in Asheville’s technology vision calls for making

the city an outpost for large technology companies — the Oracles or

Microsofts of the world — who may view a small satellite office in

Asheville as the perfect vehicle for rewarding “high value”

employees they’d like to retain. The objective is admittedly

something of a stretch, but one that could well catch fire if the city

could just land its first big-name tech firm. “Our credibility as an

up-and-coming tech center would immediately rise,” Foltz predicts.

Yet, for the time being, most seem content working to land the smaller

firms like e-Worker, then watching them blossom. At a time when many

tech start-ups are stumbling, e-Worker is signing lucrative contracts

with state Medicaid programs and forming partnerships with major names

like EDS and PeopleClick. Year 2001 sales figures are expected to

triple last year’s, according to Rick Purcell. That is certainly

music to the ears of Ian MacDonald, who doesn’t relish a return to

the hurly-burly of Atlanta, Northern Virginia or another crowded tech

center. Having just purchased a 100-year-old home in nearby

Waynesville, he and his family are settling in for what they hope will

be the long haul.

“We’re realistic about what can happen, good and bad, in the

technology industry,” he says, taking his gaze momentarily off the

autumn foliage. “Hopefully, this will be the last stop for us.”

Return to magazine index

|

|