Tar Heel Travels

Grandfather

Mountain

How Hugh Morton turned a rugged

mountain peak into a tourist attraction

By

Fill F. Hensley By

Fill F. Hensley

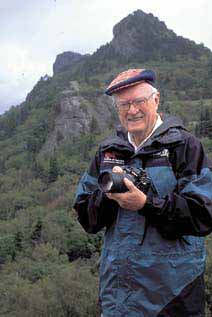

Hugh

Morton wasn’t the least bit sure that he was doing the right thing

in 1952 when he borrowed $30,000 to widen and lengthen the gravel,

single-lane road on Grandfather Mountain. But he charged a dollar a

car to traverse to the rugged peaks of the highest mountain in the

Blue Ridge range, and he got his money back within a year.

“I was dumbfounded one day in the mid-fifties when Joe Lee Hartley,

the longtime mountain manager, called to say we had taken in a

thousand dollars that day,” Morton recalls. “Until that time, the

mountain had never made any money.”

Morton had inherited the 5,964-foot high mountain near Linville a year

earlier from his grandfather’s estate after the nine heirs of Hugh

MacRae, who had developed Linville and Wrightsville Beach, had opted

for other properties owned by the 85-year-old entrepreneur who died in

1950. After all, no one wanted to pay taxes on 5,000 acres of

undeveloped mountain terrain with little chance of the land producing

any revenue.

But Morton was a mountain man and had been since he was a youth.

Owning a mountain, though not a lifetime dream, suited him fine, and

he foresaw it as a major travel attraction for the Southeast.

Along with the new road that went to the top, Morton also built a

228-foot steel suspension bridge between two rocky peaks and called

it, at the suggestion of friend Charlie Parker, a “mile-high

swinging bridge” as a main attraction. From atop the lofty mountain

and the bridge, visitors enjoyed breathtaking panoramic views that

stretched for a hundred miles in all directions.

Grandfather Mountain became an instant hit.

“A vast majority of mountain visitors come for the scenery and cool

weather,” Morton says. “We had that, but we felt that we had to

provide more for Grandfather to remain a premier destination with a

steady growth pattern.”

Native son Hartley had started the “Singing on the Mountain,” a

colorful and foot-stomping gathering of gospel performers and fans in

1924, and the Highland Games and Gathering of the Scottish Clans began

in 1955.

“These events proved to be very popular,” Morton says, “so we

knew that entertainment such as this is what the public wanted. We

tried to build and enhance those special projects over the years and

add other crowd-pleasing amenities as we went along.”

Over the years the majestic mountain has featured a variety of things

to see and do, including hang gliding; 30 miles of scenic hiking

trails; a unique, spacious natural animal habitat where visitors can

get a close-up view of bears, deer, eagles, otters and cougars; a

large nature museum that displayed native flora and fauna, minerals

and precious stones; a restaurant and gift shop; interesting seminars

and lectures; photo clinics; picnic areas and wildflower plantings.

Along with the swinging bridge, the most popular Grandfather Mountain

attraction was Mildred the Bear, which from 1966-93 became one of the

world’s best-known and loved mascots. The story of her death at age

27 was carried in newspapers throughout the United States and Europe.

Morton produced a photo-story book about Mildred shortly after her

death, and more than 60,000 copies have been sold.

“Mildred thought she was human, not a bear,” Morton recalls.

“She sensed that she was special and played her role to the hilt.

The kids loved her playful antics and her relationship with her many

lively offspring who scampered all over their habitat.”

Last year more than 250,000 people visited Grandfather Mountain, a far

cry from the few thousand who first tried out the new road and

swinging bridge nearly 50 years ago.

But Morton’s work has not ended. He is now faced with preserving,

rather than promoting, the mountain he loves so dearly, and is in

daily contact with environmentalists, scientists, government officials

and political leaders looking to find a way to stop the deadly air

pollution that is killing thousands of trees annually.

His color photos of Grandfather and surrounding mountains reveal large

streaks of dead trees whose brown foliage will never be green again.

“Our mountains are slowly dying, and our coast is being destroyed by

erosion,” he says. “We have serious problems that must be solved

to protect the natural resources that make our state so beautiful and

so unique.”

Morton’s grandfather, who acquired the mountain in 1885, would be

proud of what has transpired since he roamed the tall cliffs and

fertile valleys around Linville as a young college-trained engineer.

But mostly he would brag about the grandson who made it all happen.

For more information, call 1-800-468-7325 or visit www.grandfathermountain.com.

Return to magazine index

|

|