Cover

Story

Sky Kings

Chasing deals and serving far-flung clients

requires speed, which is why more business

people are taking to the clouds

By Lisa H. Towle

Learn More:

Why

It's a Pleasure to Fly on Business

New

Aviation Technology to Debut in North Carolina |

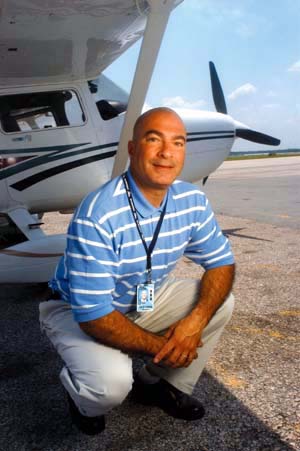

“Whenever

possible I fly, and that includes to meetings, It’s great when you can

do that because it means you can leave when you want, get to your

destination quickly, do your business and get home. You’re not stuck

in airports or in traffic, and you don’t have to spend the night

away.”

Steve Zaytoun

(left), a Cary insurance broker Steve Zaytoun

(left), a Cary insurance broker

Concord Regional Airport, which many believe is

the best way to get to Charlotte, has grown into one of the business general

aviation airports in the U.S., with some 89,000 landings and takeoffs annually.

Land at Your Front Door: Your own

air strip is the hottest thing in amenities at upscale residential

developments, such as Elk River in the mountains, which also offers great

golf. |

Paul

Barringer has spent the past 50 years with his head in the clouds, and it has

paid off big time for the chairman and CEO of Coastal Lumber Co. From his

headquarters in rural Weldon in Halifax County, Barringer has grown Coastal into

the largest exporter of hardwood lumber in the United States, with 34 mills

stretching from New York to Florida, Alabama to West Virginia. How does he

manage such a far-flung enterprise? He flies a lot, often at the controls of one

of the company’s three planes. Paul

Barringer has spent the past 50 years with his head in the clouds, and it has

paid off big time for the chairman and CEO of Coastal Lumber Co. From his

headquarters in rural Weldon in Halifax County, Barringer has grown Coastal into

the largest exporter of hardwood lumber in the United States, with 34 mills

stretching from New York to Florida, Alabama to West Virginia. How does he

manage such a far-flung enterprise? He flies a lot, often at the controls of one

of the company’s three planes.

“I built Coastal Lumber up by flying. We’ve grown primarily by using

aircraft to access growth opportunities and markets,” says Barringer (left)

. The joke

around the company is that the boss never buys a plant that doesn’t have air

access. Except it’s not really a joke.

Barringer’s formula for business success is elegant in its simplicity: Get

there first, get there fast. Many lumber mills are located in mountain or

coastal areas far off major roads. As soon as Coastal Lumber gets wind that a

mill they might be interested in is for sale, a company executive gets on a

company plane in a bid to be the first on the scene and so the first to seal the

deal. Likewise, if there are problems at a plant that need to be quickly

addressed or customers, bankers or insurers who need to be transported, the

planes and their professional, salaried flight crew — or Barringer himself —

are ready to takeoff.

“I believe in showing the flag,” says Barringer. “Management visits mills

every week. We can do this because we have one- or two-hour flights versus, say,

eight- or 10-hour drives.” Each airstrip with which Coastal does business

keeps a company car at the ready so its employees and associates don’t have to

worry about ground transportation.

It’s a winning strategy — Coastal Lumber’s annual sales exceed $350

million — though not an inexpensive one. The company’s lifeblood — its

three aircraft (prop jets and a smaller twin engine plane used to get into

smaller airstrips) — cost millions. Factor in hangar space and maintenance at

the base site, Halifax County Regional Airport in Roanoke Rapids, and soon

you’re talking about real money.

But it’s money well spent, says Barringer, “Once you analyze the

opportunities it (general aviation) presents — flexible scheduling, speedy

deals and problem resolution, tremendous customer service and marketing

advantages, among other things — the advantages come out to many times the

investment in the planes.”

Roger that, says 46-year old Steve Zaytoun, an aviation enthusiast since

childhood and a licensed pilot since 2000. “Whenever possible I fly, and that

includes to meetings,” explains Zaytoun, whose Cary-based insurance company,

Zaytoun & Associates Inc., has clients statewide. “It’s great when you

can do that because it means you can leave when you want, get to your

destination quickly, do your business and get home. You’re not stuck in

airports or in traffic, and you don’t have to spend the night away.”

The Sky’s the Limit

Business executives like Barringer and Zaytoun are the human faces behind

statistics showing a rapid rise in the number of pilots and the robust health of

the general aviation marketplace. At the end of April 2003, for instance, the

Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA), the world’s largest civil

aviation organization, had nearly 400,000 members. That number has grown by

30,000 in the year and a half since the terrorist attacks on the United States.

The Federal Aviation Administration expects the U.S. pilot population to grow to

nearly 825,000 by 2011. With its 14,882 aviators, North Carolina ranks 13th

nationwide in the number of certificated pilots.

Another barometer of the health of general aviation is the increased activity in

North Carolina’s airport system, which has been evolving since the 1920s when

the General Assembly enacted the first statutes to guide airmen and local

governments in their aviation-related activities. Today, a network of 74

publicly owned airports, nine of which have airline service, means there’s an

airfield within 30 minutes of all population centers in the state.

While commercial air carriers have suffered mightily in the wake of 9/11,

general aviation —defined as all flying except that of the scheduled airlines

and military — has grown at a healthy clip. A measure of that growth can be

attributed to the terrorist attack backlash effect. The things that have always

made GA appealing — speed, flexibility and privacy — are even more

attractive to business people in the age of homeland security and consequent

disrupted schedules.

According to the AOPA, two-thirds of all GA flight hours involve business,

commercial, instructional and public service operations. The remainder of the

hours is devoted to personal travel. Further, an estimated 65 percent of general

aviation flights are conducted for business and public services that need

transportation more flexible than the airlines can offer.

The ripple effect of these airports is very real. Nationally, an immense fleet

of general aviation aircraft is the mainspring of a $20 billion a year industry

that generates more than $102 billion in economic activity. Becaue of how

information is reported, it’s difficult to calculate the financial impact of

GA within North Carolina. Given what is known, though, extrapolations can be

made. Ninety-five percent of the roughly 220,000 civil aircraft registered in

the U.S. are general aviation aircraft. There are 7,815 aircraft — general

aviation and otherwise — registered in the state (as opposed to aircraft based

in North Carolina, a larger number but harder to pinpoint). And aviation in

general contributes somewhere between $10 billion to $11 billion a year to the

state’s economy, says Bill Williams, director of the N.C. Department of

Transportation’s aviation division.

“No matter how you look at it,” adds Williams, “airports are definitely an

economic engine and tool for all regions in the state.… They make the country,

the world, a much smaller place.”

Business people like the fact that they can take advantage of rapid, on-demand

air transportation, he continues, and the air access helps attract corporations

that wouldn’t consider locating a plant, headquarters or distribution center

in an area without access to air transportation.

The Best Way to Charlotte

Access is a subject that comes up time and again when you ask business people

why they fly their own planes. Access also is the reason behind the stunning

growth of several regional airports across the state, which often are situated

close to major metro areas.

That’s why Concord Regional Airport — which didn’t even exist a decade ago

— has grown into one of the busiest general aviation airports in the United

States, with some 89,000 landings and takeoffs a year. Concord officials

actively promote their airport, which is located about 15 minutes from the

corner of Trade and Tryon, as the fastest way in and out of Charlotte.

Concord Regional also is minutes from Lowe’s Motor Speedway, the undisputed

epicenter of NASCAR, and its proximity to I-85 places it in the heart of the

highest growth corridor in North Carolina.

NASCAR is just one example of an industry that has heavily utilized general

aviation, and city officials actively encourage other businesses and industries

to follow its lead. A $13.3 million multi-phase, multi-year expansion program at

Concord Regional, whose centerpiece is a runway extension, signals they’re

making headway. The benefits of extending the runway by 1,900 feet are not just

improved safety and performance of planes but also the leverage Concord will

have when negotiating with potential customers.

Federal monies pay for the bulk of airport construction and their expansions.

Steve Merritt, an aviation program officer with the state’s aviation division,

says the funding breakdown is typically 80 percent federal, 10 percent state and

10 percent local. Maintenance expenses, like those for libraries and

recreational facilities, fall to local entities. “Those costs aren’t

considered an undue burden, though, because airports are viewed as assets,”

adds Merritt.

Lee County is a poster child for another aspect of general aviation: that having

a regional airport can be a key component in a local area’s economic

development infrastructure. Over the past two decades or so, Lee has progressed

from a grass airfield to a full-fledged airport. All that work and investment

paid off in October 2000 when the FAA determined that Raleigh-Durham

International needed relief from its traffic load. The all-new Sanford-Lee

County Regional was well positioned to take the overflow

Home to corporate aircraft, recreational aviators and an active flying club, the

airport, located on 700 acres within a half mile of U.S. 1, was built with 80

percent federal funds, 16 percent state funds and 4 percent local funds. It’s

valued at $9.5 million by the Lee County tax assessor, and brings the county and

the fire district in which it’s located more than $73,000 in combined real

estate taxes alone.

“The (personal) property tax on the (75 to 80) airplanes based at the airport

account for another big and direct financial benefit to Lee County, but the

transient planes, like the ones from Caterpillar or Wyeth that bring in

executives and freight, also contribute because they pay a 2 percent local sales

tax on fuel,” says Dan Swanson, manager of the airport, where a new corporate

hangar is rising for an undisclosed company in western Wake County that wants

ready access to its plants across North America.

The Multiplier Effect

And there’s something else that should be considered when factoring the impact

of GA on a region, says Tim Deike, director of Hickory Regional Airport. It’s

the multiplier affect. That is, what’s spent on meals, hotels and gasoline by

those who fly in to work or play.

While seeking to replace the commercial service it lost in April 2002 when US

Air withdrew from the market, Hickory Regional stays busy with the general

aviation needs of 11 counties whose combined populations total about 750,000.

Its primary users are some 100 corporate and private aircraft, tended by Profile

Aviation, the fixed base operator. In mid-July, Profile anticipates moving into

a new building complete with meeting facilities. Planning is under way for

extensive renovations to the passenger terminal, and negotiations are

progressing with a commuter airline to offer daily service to Raleigh-Durham

International.

On the table are several other ideas that will help Hickory Regional continue to

serve both the flying and non-flying public: Establishing a discount flight

service that would pull from the Charlotte market; building a hangar for N.C.

Forest Service aircraft used for forest fire operations; and developing a

facility for the display of vintage airplanes.

As reflected in Hickory’s plans, GA can be a critical part of other business

enterprises. They include aerial advertising; aerial surveying, exploration,

environmental surveys; agricultural application; business and corporate

transportation; emergency evacuations and rescue missions; fire spotting and

fire fighting; law enforcement; map making; medical transportation or emergency

flights; news reporting, photography, videotaping, and traffic monitoring;

on-demand air taxi service; overnight mail and package delivery; personal

transportation; pipeline and power line patrol.

Indeed, with about 95 percent of the civilian aircraft in the U.S. general

aviation planes and just 4 percent scheduled airliners, Hickory Regional’s

Deike never fails to be amazed that “when people think ‘transportation’ or

‘transportation and business’ they don’t automatically look to the sky.”

New

Aviation Technology to Debut in North Carolina

In a special edition of Time magazine devoted to the 100 people who most

influenced history over the past 100 years, Bill Gates, chairman and CEO of

Microsoft, wrote about Wilbur and Orville Wright. He said that powered flight

“… effectively became the World Wide Web of that era, bringing people,

languages, ideas and values together. It also ushered in an age of

globalization, as the world’s first flight paths became the superhighways of

an emerging international economy. Those superhighways of the sky not only

revolutionized international business; they also opened up isolated economies. .

. . ”

All that from little noticed but ultimately successful experiments that took

place on the isolated, windswept dunes of Kitty Hawk. Now in this the 100th

anniversary year of manned flight, North Carolina is on the brink of another

aviation first with far-reaching implications.

If all goes as planned, by the end of 2004 the state will be the first in the

lower 48 states to have installed statewide a new air safety technology known as

ADS-B. Tested in Alaska, ADS-B, which stands for automatic dependent

surveillance-broadcast, will provide pilots with real-time, graphic and textual

updates about traffic, weather and eventually even surrounding airspace. The

information will get from ADS-B ground stations to cockpits via Universal Access

Transceiver datalink technology.

In mid-May, North Carolina aviation officials, including state aviation director

Bill Williams, visited the Frederick, Md., headquarters of the Aircraft Owners

and Pilots Association to see the technology in action.

The AOPA, which has helped the Federal Aviation Administration develop the

technology, regards it as “part of the air traffic control system of the

future.” But, cautions Williams, a system can have little effect on air safety

unless pilots use it.

Sounds familiar, just as when, wrote Gates, “the Wright brothers gave us a

tool, but it was up to individuals and nations to put it to use. . . . ”

— Lisa H. Towle

Why

It's a Pleasure to Fly on Business Why

It's a Pleasure to Fly on Business

Nov. 1, 1999, is a date etched into Steve Zaytoun’s memory. That’s when he

and a friend, Carl Ferland, owner of a dozen Denny’s franchises in North

Carolina and South Carolina, decided the time was right to explore their mutual

interest in aviation. They visited Southern Jet, a fixed base operator at

Raleigh-Durham International (RDU) that also offers flight training.

Ferland received his pilot certificate in September 2000 and Zaytoun (left), president

of Cary-based insurance brokerage firm Zaytoun & Associates, got his a month

later. Both men now own single engine planes that they keep at Southern Jet.

Zaytoun, who was taught by Steve Merritt, a pilot and certificated flight

instructor working out of RDU and the Johnston County Airport in Smithfield,

flies his Cessna about three times a week When asked is he flies mostly for

business or pleasure, he laughs and says, “They’re one in the same.”

That’s a common reaction, says Merritt, who also works as the WorldFlight 2003

coordinator for the state’s Division of Aviation. “Businesses may benefit

from the fact that the people who run them are pilots, but do those people learn

to fly for that reason? No. They do it because they want to fly, period.”

Two trends have come together to make it easier for business people to become

pilots. In the mid-1990s, thanks to a reform of aviation insurance laws, the

general aviation industry began pulling out of a slump it had been in throughout

the ’80s. With more favorable liability rules in place, manufacturers began

producing more aircraft.

And to ensure that there was a market for all these new planes in the market,

the aviation community launched the Be A Pilot program to teach people to fly.

Run by a coalition of the entire aviation community, Be A Pilot offers $49

introductory flight lessons through flight schools across the country, including

55 in North Carolina. The idea behind this, of course, is that once someone has

experienced flight from a cockpit they’ll never turn back. For the most part,

things have gone according to plan.

Zaytoun is one who never looked back after Nov. 1, 1999. He’s now working

toward his instrument rating so he can use cockpit instruments and won’t be

restricted to flying under visual flight rules. Next will come the commercial

designation. Some one-third of general aviation pilots who fly small planes hold

a commercial, rather than private, pilot certificate.

After that, well, the sky’s the limit. Zaytoun can see himself retired from

the insurance business, the owner of a twin-engine plane, flying charters to the

men’s NCAA Final Four basketball tournaments and to various tropical

destinations. — Lisa H. Towle

|

Landing at

Your Front Door

Like avid golfers who choose to live on

a golf course, business

people who fly have

fueled the existence of 'fly-in communities'

A private

airstrip at Elk River is a popular amenity for homeowners at the

upscale Banner Elk country club |

Although

it helps, you don’t have to be rich to become a pilot and own your own small

plane. Heck, most pilots don’t even own the plane they fly. Most rent one by

the hour or share expenses with other pilots. In fact, according to the Be A

Pilot program, “many pilots spend as little as $1,500-$2,000 a year on flying

— what other people may spend on skiing, golf or other pursuits.”

Be that as it may, it does require disposable income to fly, and some pilots in

the higher tax brackets are at the forefront of a trend that marries air strips

and real estate. Like avid golfers who choose to live on a golf course, business

people who fly have fueled the existence of “fly-in communities.”

Indeed, North Carolina has a dozen or more such upscale developments that come

with private airstrips or airparks within an easy walk of your front door. The

list includes Aero Plantation in Weddington, Eagles Landing Airport in

Pittsboro, Elk River in Banner Elk, Goldhill Airpark in Goldhill, Lake Norman

Airpark in Mooresville, Long Island Airport in Terrell, Marchmont Plantation

Airport in Advance, Mountain Air in Burnsville, Pilot’s Ridge in Wilmington,

Seven Lakes in West End, Stag Air Park in Burgaw, and Tuckasegee Airpark in

Hayesville.

Steve Merritt of Wake County, a longtime pilot and certificated flight

instructor, is taking the concept of “fly-in communities” one step further.

He’s developed the idea of “hangar homes” for the Brunswick County

Airport, and is working through the approval process. What he’s proposed for

initial development is a 2,000-square-foot hangar topped by a 2,000-square-foot

home. Motor vehicles would also be parked under the residences.

Such hangar-home combinations exist elsewhere in the country, but not in North

Carolina. Anticipating questions, he’s quick to point out that the sound of

planes is music to the ears of pilots; that access to an airport would be

controlled either by card or keypad entry through a security gate; and that

regional airports, which grow quiet after darkness falls, would benefit from the

activity of residents.

Merritt estimates that the units would sell for $300,000 each. Quoted recently

in The State Port Pilot about the project, the airport manager Howie Franklin

called that amount the “low end” of a growing housing trend. -- Lisa H.

Towle

Return

to the magazine index

|