|

Tar Heel

Travels

Blue Ridge Parkway

Why it took 52 years to complete

'America's most scenic drive'

By Bill F. Hensley

It

is known around the world as “America’s most scenic drive,” and there is

little argument in bestowing that prestigious title on the famed Blue Ridge

Parkway, the spectacular route that traverses from Virginia through North

Carolina and connects two popular national parks. It

is known around the world as “America’s most scenic drive,” and there is

little argument in bestowing that prestigious title on the famed Blue Ridge

Parkway, the spectacular route that traverses from Virginia through North

Carolina and connects two popular national parks.

“I don’t know of a more beautiful drive anywhere on earth,” says veteran

travel writer Jim Wamsley of Richmond, Va. “It has everything: the majestic

blend of forest, mountain and waterfall; fascinating flora and fauna; a colorful

mountain heritage; places to stop and enjoy. Gaze from the overlooks. Hike into

the wilderness. Go camping. Take side trips. You will be overwhelmed, as I

always am.”

For the record, the Parkway stretches for 469 miles and covers 80,000 acres

along the rugged crests of towering mountains. It begins at the south entrance

of Shenandoah National Park and ends in Cherokee, where the Great Smoky

Mountains National Park begins.

The Parkway is as much a part of North Carolina as basketball and barbecue, and

its 22 million annual visitors make it the most visited of all national parks.

And it’s a moneymaker, as tourism generated $2 billion last year for the 18

western counties that use the thoroughfare as a major transportation artery.

“The Blue Ridge Parkway is a national treasure,” says Hugh Morton, the owner

of Grandfather Mountain, who played a key role in the road’s history and

development. “There’s never a day that I don’t thank the good Lord for

this priceless asset. Very few states can claim anything that comes close to

equaling the Parkway as a travel attraction.”

The idea of a picturesque drive along the state’s mountaintops originated in

1906 with a geologist named Joseph Pratt, who proposed a toll road from Marion,

Va., to Tallulah, Ga. After securing a charter for the Appalachian Highway Co.,

construction began in 1914 between Altapass and Pineola, N.C., but was brought

to a halt by the outbreak of World War I and was never resumed.

The chief inspiration for the Parkway came from the building of the Skyline

Drive through Shenandoah National Park. The depression-era project quickly

generated national publicity and interest, and when President Franklin D.

Roosevelt visited in 1933, he was urged to extend the route to the new Great

Smoky Mountains National Park. The president liked the suggestion and was backed

by the governors of North Carolina, Virginia and Tennessee.

Interior Secretary Harold Ickes approved the new highway as a public works

project and authorized $4 million in funds. After the routing had been approved,

landscape architect Stanley Abbott of New York was hired to direct the design

and planning. Work began in September 1935 on a 12-mile stretch near Cumberland

Knob in North Carolina.

Because of delays, the Parkway — officially named the Blue Ridge Parkway by

Congress in 1936— was divided into 45 separate construction units. The work

was done mostly by private contractors, but the Works Progress Administration

was involved in order to provide employment for as many men as possible. Workers

earned $55 a week.

When World War II started, construction funds were impounded and work came to a

halt. At the time, 170 miles had been finished and another 160 miles were

partially completed. The price tag stood at $20 million.

Post-war work was slow to resume because funds were limited, but by the

mid-1950s about half of the Parkway had been completed. Work moved faster during

the next decade, and at the end of 1966 only 7.7 miles remained unfinished. But

it took another twenty years, however, for the “missing link” on Grandfather

Mountain to be built and to complete the project after 52 years.

The argument over where to build the unfinished section was long, often heated

and emotional, and took place in federal and state government circles. Federal

engineers wanted to take the Parkway across the top of the privately owned

mountain, but Morton — the owner and an arch conservationist — and his avid

supporters rightfully declared that such a routing would require too much land

and would seriously damage the natural beauty of the terrain. They held out for

a “middle route” that would do minimum damage and be less costly, yet would

be in keeping with the integrity of the project.

Strongly backed by the administration of governors Luther Hodges, Terry Sanford

and Dan Moore, Morton finally won his intense battle, although the missing link

wasn’t completed until 1987.

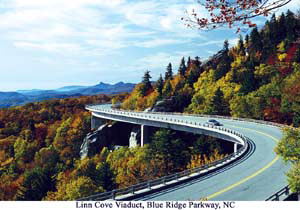

Today, the stretch around Grandfather — highlighted by the architecturally

significant and award-winning Linn Cove Viaduct — is one of the Parkway’s

most spectacular sections and has drawn national acclaim for its superb

engineering and esthetic marvels.

The awesome natural beauty of this leisurely drive, preserved in all its glory,

is proof that man, nature and government can work in harmony.

For more information on the Blue Ridge Parkway, contact the National Park

Service or the Blue Ridge Parkway Association at P.O. Box 2136, Asheville, N.C.,

28802, or visit www.blueridgeparkway.org.

Return to

magazine index

|