|

|

“He

took two elections that were almost certain defeats

and turned them into victories. The first saved Ronald Reagan’s

political career in 1976 and the second saved Jesse Helms in

1984.”

-- Carter Wrenn, former staff

director of the Congressional Club. |

Executive Profile

True Believer

Tom Ellis, the strategist who got Jesse

Helms elected, likely is the most influential politician never to hold

office

By Ned Cline |

|

Tom

Ellis was a 19-year-old freshman football player at Dartmouth College in New

Hampshire one subfreezing December day in 1939 as he watched classmates craft an

ice sculpture on the campus lawn.

“That darn thing was still there the next May, hadn’t melted a bit,” Ellis

recalled recently. “I wasn’t really satisfied at Dartmouth anyway, and when

I saw that block of ice hanging around for so long I knew it was time for me to

get out.”

And he did. He came as far south as Virginia Beach the next summer and met some

friends who spoke of the virtues of North Carolina in general and the University

of North Carolina in particular. In the fall of 1940, Ellis became a Tar Heel.

It would be too simplistic to say that the rest is history. It would not,

however, be an exaggeration to say that as a North Carolinian Ellis helped make

and change history in this state. Republicans and other conservatives here can

be thankful for that blustery New England winter that drove Ellis this way.

Among North Carolina’s political insiders, Ellis is an icon who either wears

angel’s wings or carries a devil’s pitchfork, depending on one’s

particular political perspective. Outside those insiders, however, he’s still

not a household name because he has functioned for decades primarily as this

state’s stealth political fighter pilot.

Ellis is to conservative political thinking what Arnold Palmer once was to golf:

the master with a sweet stroke who knows how to win.

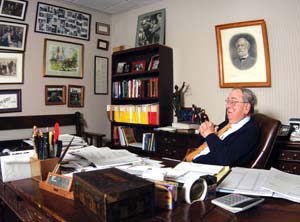

A Raleigh lawyer by profession and a respected political strategist by

avocation, Ellis is arguably the single most significant promoter of

conservative philosophy in this state in the last half century. He has truly

altered the course of history in North Carolina and beyond, seldom with fanfare

and never for personal gain. He genuinely believes in the conservative cause.

He’s 83 now, but age hasn’t curbed his zeal.

That’s just one side of the man. There is another, known only to his family

and close friends because that side is even more private than his political

alliances. He is a person of deep religious faith, a disciplined and caring

father and grandfather, founder of a private school, devoted golfing and jogging

buddy, mentor and confidant, and a man who shuns all things extravagant. His

“aw shucks” personality is as genuine as his political philosophy.

He has kept most of the same golf partners for decades. “We just keep the same

group until one dies off, then replace him,” Ellis says with a truthful grin.

His partners call him a serious golfer, as determined to win as in politics. He

once (but only once) shot a 70. He formed a jogging club 40 years ago at N.C.

State, and has stuck with it. He has been participating in a regular Bible study

course for more than 15 years.

Ellis lives in a house he built in 1956 on what was then a dirt street one block

off Glenwood Avenue in Raleigh. He is notorious for driving used cars, most

notably a dilapidated Volkswagen beetle that eventually died only after the

rusted frame literally began dropping engine parts onto the street. He

reluctantly sold the vehicle for $10. He and his wife now drive Cadillacs, but

never new ones. When she insists on a newer used model, he takes her older one

for his own.

“Clothes, cars, and cash never mattered much to him,” former Raleigh Mayor

Tom Fetzer says of Ellis. “He never collected a dime for all his years of

political work even though he is a strategic genius of unquestioned integrity

with an intuitive connection to the populace.” When he spent large amounts of

time on political activities, Ellis routinely asked his law partners to reduce

his share of their firm’s annual income.

Ellis’ former campaign associates conservatively estimate he dedicated the

equivalent of six full years to campaigns during the last three decades, all

without pay. “The media has portrayed him as an uncaring person with a short

horizon,” says Raleigh political consultant Mark Stephens, “but he is just

the opposite. He is a visionary, thoughtful and generous, cares deeply about his

family and others and in his heart does what he honestly feels is best for

America, both personally and professionally. He has been a wonderful mentor to

many.”

Most of the accolades about Ellis, not surprisingly, come from Republicans. But

not all. “I love Tom Ellis,” says Ken Eudy, a Raleigh public relations

company owner and former executive director of the N.C. Democratic Party. “He

is a good friend and a straight shooter. You can always count on him to be

honest.”

It is a truism to say that Ellis created Sen. Jesse Helms — thus the angel

wings or pitchfork assessment — because without Ellis, there would never have

been a Sen. Helms. Ellis convinced Helms to run for that high office and crafted

the successful Helms campaigns. The two were joined at the political hip for

more than 30 years. That relationship has soured now, for reasons unrelated to

political philosophy because they’re still in tandem on that, but Helms

willingly gives Ellis deserved credit for his victories.

“Without Tom Ellis, I would never have been a senator,” Helms said recently,

acknowledging that the two don’t see much of each other now even though

they’re both in Raleigh. “I like him and would still trust him with my

life.”

While it is generally agreed among friends of both Ellis and Helms that the two

complimented each other in campaigns because they were committed to a common

cause, it is also conceded that Ellis is likely stronger without Helms than

Helms is without Ellis. “Would Paul Newman have been such a good actor if he

had not had a good director?” one friend of both men asks rhetorically.

Ellis was the braintrust behind creation of the National Congressional Club that

raised and funneled many millions of dollars into and mapped strategies for the

Helms campaigns over three decades.

Helms, however, is just one of the

winning hands in Ellis’ political deck of cards. Others in this state have

included Sen. John East, Sen. Lauch Faircloth, Lt. Gov. Jim Gardner, Cong. Bill

Cobey and Fetzer, the former Raleigh mayor.

As significant as some of those have been in shaping this state’s political

landscape, with Helms the focal point, Ellis’ most important winner for

conservatives was Ronald Reagan. Ellis has seldom received much recognition for

his role in Reagan’s political survival, but that doesn’t negate its

national impact or the cunning way he successfully carried it out.

Without Ellis, there likely would never have been a President Reagan. In 1976,

Reagan had lost all the early Republican presidential primaries against Gerald

Ford and North Carolina was his last hope. Prospects here appeared dismal as

Reagan’s national political advisers clawed for support against Ford and the

state’s entrenched Republican establishment led by then Gov. Jim Holshouser.

The Reagan prospects just weeks before the North Carolina primary were so

depressing that the candidate had privately prepared himself for defeat and,

running out of campaign funds, decided to leave the state after losing and

return to California, turn in his rented airplane and drop out of the race.

Ellis had other ideas. He felt Reagan’s national campaign staff didn’t

understand the electorate in North Carolina and not so diplomatically ordered

Reagan’s national campaign aides to back off. Ellis effectively took command

of the campaign in the state, privately and quickly raised money for some last

minute straight-talk TV ads — which Reagan’s sulking staff thought were

silly — and talked up conservatives issues he felt would resonate with voters

here. It worked. Reagan, in a shocker to almost everyone but Ellis, won here and

his candidacy was saved.

It took Reagan another four years to win the presidency, but the victory in

North Carolina kept him as a viable candidate. Without Ellis snatching victory

from defeat, Reagan would have quit, perhaps never to run again. Many others

across the country, of course, helped Reagan later win the White House, but it

was Ellis that kept him on political life support.

“I can’t really place a value on all I learned from Mr. Ellis,” says

Carter Wrenn, former staff director of the Congressional Club. “But he took

two elections that were almost certain defeats and turned them into victories.

The first saved Ronald Reagan’s political career in 1976 and the second saved

Jesse Helms in 1984 (in a hard fought campaign against then Gov. Jim Hunt).”

“My only interest has been to get conservatives elected,” Ellis says of his

quiet campaign roles. “I think I did that. That’s all I wanted. I know it

sounds trite, but I just thought I could make a difference.”

“I guess I have always been conservative,” he adds. “Those are the

principles that built this country and made it great. I know you have to have a

national government, but sooner or later you’ve got to have a reckoning.

Little by little, I think we’re inching toward socialism and that will lead us

to destruction. It’s all in what you believe in and what you care about.

“The problem is that too many politicians run on popular approval and they

listen to whoever is holding the biggest megaphone. I think (President George

W.) Bush and (political advisor Carl) Rove are reading the opinion polls right

now. I still have faith in the people and believe if you are doing the right

thing, most voters will support you. I don’t like political phonies.”

Ellis’ political opponents have called him many things, but phony is never one

of them. Genuine is the word most used to describe him, regardless of political

persuasion. And despite his concern about what he calls the leftward flow of the

political pendulum, his passion that right will prevail is more pronounced than

his pessimism.

That trait started a long time ago. He didn’t learn conservative philosophy at

his daddy’s knee, but his first lesson did come at home.

Ellis’ father, William Robert Ellis, was a vice president of Hercules

Power, the company that later became DuPont Corp. As an engineer who helped

design the Hoover Dam, the senior Ellis was schooled in the rabid anti-New Deal

philosophy of the DuPont family. The father’s job and ties to company

headquarters brought the family from California, where his son was born in

August 1920, to Wilmington, Del., in the mid-1930s.

Shortly after enrolling at UNC and beginning his study of finance, Ellis went

home one weekend and began discussing a labor law class in which he had been

told that management oppressed workers in big businesses. “My father sat me

down and told me what the score was,” Ellis says. “He explained that I had

it all wrong.” That was the beginning of the Ellis conversion to conservatism.

Sixty years later, it’s still strong.

While a student in Chapel Hill, Ellis met his future wife, Jinette Hood, a

student at St. Mary’s College in Raleigh. Her father, a Virginian, was as

conservative as Ellis. In 1964, with a UNC degree in hand, he married and took

his new wife to California during his two-year stay in the U.S. Navy where he

taught radar courses. He calls it a two-year honeymoon.

Determined not to return to the frigid north, Ellis enrolled at the University

of Virginia Law School and excelled, earning a degree in three years in 1948.

“I liked the South and wanted to stay here,” he says.

Choosing Raleigh to start a career, Ellis opened a solo law office. In 1950, he

teamed with attorney Joe Cheshire in a two-person firm and promptly made his

first venture into political activism as a researcher for U.S. Senate candidate

and fellow Raleigh lawyer Willis Smith in his campaign against Sen. Frank Porter

Graham. That is when Ellis first met Jesse Helms.

That campaign, bitter to the end, convinced Ellis of two things: he was

determined to continue in the political arena and he needed a new law partner.

Cheshire was as strong for Graham as Ellis was for Smith.

Ellis then joined what would become one of Raleigh’s most respected law

practices at Maupin, Taylor and Ellis. The firm’s major clients over four

decades have been railroads and other large corporations where partners earned

the title of “union busters,” although Ellis was always as diligent in

representing indigent individuals as big businesses.

A year ago, with senior partners and longtime friends Armistead Maupin and

William “T” Taylor effectively retired, Ellis left the firm to join

Haynsworth Baldwin Johnson & Greaves with offices in Cary and Greenville,

S.C. The Haynsworth name may register with conservatives. Partners in the law

firm are relatives of Clement Haynsworth, the conservative South Carolina lawyer

who Richard Nixon unsuccessfully tried to appoint to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Ellis still works almost every day at the law office. Among the pending cases he

is in the thick of at present is the legislative redistricting battle in North

Carolina.

The Ellis influence can also been seen beyond the ballot box. While he never

accepted a dime of pay for any of his political work, his shadow looms large

over federal courts. His recommendations for federal judges have resulted in at

least three sitting jurists in North Carolina: Terrence Boyle (Ellis’

son-in-law), Mac Howard and Frank Bullock. “Jesse (Helms) asked me after he

won the first time what I wanted and I told him nothing except I would like to

recommend some good people for judgeships,” Ellis says.

“He has always treated me like a son,” Boyle says, “and his force of

impact on this state and nation is tremendous. His pedigree is like a CEO, but

he has never wanted anything official. He has won virtually ever hand he has

played, but never picked up the pot. He has a compelling drive and force of will

for his beliefs. That’s a tribute to the man.” Boyle, like many, addresses

him only as “Mr. Ellis,” a term of endearment.

Judge Bullock, a former member of the law firm with Ellis, calls Ellis an

inspiration to others in law and politics. “He’s a great visionary, a

tenacious representative of his clients who always works to achieve what others

think is not possible,” Bullock says.

“I’ve been blessed to have him for 60 years,” Jinette says. “He’s

quite a patriot and I’m very proud of all he has accomplished.” She says she

agrees with his politics and listens to his views “most of the time.”

Ellis’ political and moral

disciplines extend to his son, Hood, an attorney, and his daughter, Debbie, who

is an artist and Judge Boyle’s wife. The siblings live in Edenton along the

North Carolina coast. Ellis encouraged them to move to a small town. “Bad

things get to small towns a little later,” Ellis says with reference to his

grandchildren. When the grandchildren visit their grandfather, they frequently

get what Jinette calls “little lectures” on societal topics and life’s

issues.

“He has been a wonderful role model for me and many others,” son Hood says.

“No one has impacted me more than he has. I suppose at one time I challenged

him on some things, but I have learned that if you just do what he says, chances

are you’ll be right.”

Ellis’ friends and associates are unanimous in mentioning integrity, fairness

and honesty when asked for their assessments. “He’s the truest friend anyone

could ever have,” says retired insurance executive William Gilliam. “I’ve

known him 60 years and never met a more honest man.”

Joe Knott, a Raleigh lawyer and leader of Ellis’ Bible Study group, calls

Ellis “highly principled” with a passion for his country, his church and

issues of right and wrong. “We don’t talk much politics,” Knott says.

“For me to talk politics with Mr. Ellis is like me talking basketball with

Michael Jordan. I can’t compete. But he is certainly one of the brightest

stars and the voice of conservative allegiances in this state.”

The best Ellis assessment, however, may be from Bob Harris, a 45-year-old

physically challenged individual with a degenerative muscular disease who has

been bedridden since 1981. Ellis first gave Harris a job, then when he could no

longer care for himself, Ellis led the effort to secure electronic equipment

essential for Harris to maintain a viable life.

“I can say Mr. Ellis is the finest gentleman I have ever known and my life

would have turned out a lot differently if I had not met him,” Harris

volunteers, speaking through a computer, his only means of communication. “I

don’t think anyone else would have given me a chance. He was also great to my

mom when she was dying. She respected him for that, and so do I.”

Return

to magazine index

|