July

2004

Cover Story

Rising Tide

The global economy is shipping

a boatload of export-import business to the state ports

By Lawrence Bivins

Tom Beard watched nearly one third of his

business go overseas after his Greensboro lumber company reacted to

international competition. But Beard Hardwoods isn’t a victim of the new

global economy, it’s a beneficiary. Beard now has major buyers in Europe and

Asia — many who are old, loyal customers. “We started shipping to Japan

about 27 years ago,” he says.

Beard Hardwoods’ success — with offices in five states, the company is one

of America’s leading wholesale hardwood lumber merchants — is a story about

globalization’s sunnier side. “The world is smaller now,” says Beard, who

is in his early 70s. “We’re in a global economy, and it’s here to stay.”

As an exporter, Beard is a vocal advocate of North Carolina’s gateway to the

world marketplace: the state ports at Wilmington and Morehead City. “Our ports

are in a great position,” he says. With congestion choking cargo traffic at

larger, more prominent port complexes in Charleston, Norfolk and Savannah,

opportunities are swirling around North Carolina’s unclogged ports, especially

now that a series of major channel and terminal upgrades is complete.

“There’s a lot of potential for our ports,” Beard says.

|

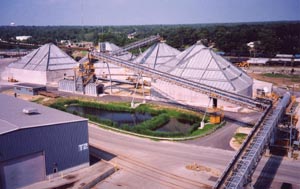

An aerial view of the Port of Wilmington |

An aerial view of the Port of Morehead City

Learn more:

Higher

gas prices drive many to find -- and enjoy -- mass transit

|

Beard, along with countless others who rely on North Carolina’s ports, can

attest to the facilities’ user-friendliness. On this May morning, Beard

watches as four container trucks depart his lumberyard for the dock at

Wilmington, where massive cranes will lower them onto awaiting vessels that

afternoon. Competing mid-Atlantic ports cannot do this, Beard says. There,

containers stack up for a two-day wait before finally getting their turn at the

crane. “None of the larger ports can offer same-day service,” Beard says.

Focused on Customers

While the two ports have been part of the state’s economy for centuries, it is

in many respects a new day for them. In the fiscal year ended June 2003, the

Wilmington facility moved more than 2.2 million tons of cargo. More than 1.5

million tons passed through the Port of Morehead City. The latter complex

specializes in bulk product, materials such as scrap steel and unprocessed wood

items that are loaded directly into a ship’s hold, and break-bulk cargo,

product that is packed onto pallets or small bins prior to loading. The

Wilmington port, which also handles this type of cargo, is “containerized.”

Much of the goods traveling through it are stored in metal rectangles that can

be transferred to and from rail cars or heavy trucks.

While the ports themselves are located along the state’s shore, the lion’s

share of the businesses they serve are Piedmont-based, like Beard’s. “Most

of the ports’ business comes from companies west of Raleigh,” says Richard

Futrell, whose five-year stint as chair of the North Carolina Ports Authority

comes to an end later this summer.

The Piedmont is, after all, the state’s dominant economic corridor. And in

order to link the region with the ports, the authority maintains cargo terminals

in Greensboro and Charlotte. The inland terminals work well for Tom Beard. “I

can call and have a container here in half an hour,” he says. What’s more,

the ports match his outgoing shipments with the arriving cargo of another

customer, freeing Beard from having to foot the cost of the round trip.

“Customer service is excellent,” Beard says.

The customer-focus displayed by port officials has helped distinguish it from

the competition. In March 2000, when WFI Sales began importing finished European

wood through Wilmington, the company found the port’s handlers inexperienced

at loading such items. “We had to overcome some logistical obstacles, but

operations personnel at the port were willing to work with us and learn our

business,” recalls Kenny Woodard, president of WFI. The company, headquartered

in Smithfield, operates out of Wilmington, Port Canaveral, Fla., and Houston,

its products winding up in the hands of big-league retailers such as Lowe’s

and Home Depot. “Wilmington is by far our largest operation,” Woodard says.

“All the folks there have been very helpful to us.”

For North Carolina firms like WFI and Beard Hardwoods, doing business with the

state ports provides real financial benefits in the form of a tax credit of up

to 30 percent of fees paid to the authority. “The tax incentives the state

offers have been invaluable,” says Woodard. While some of the handling fees he

encounters at Wilmington are higher than ones levied at other ports,

“incentives help offset some of those costs,” according to Woodard.

The convenience found by importers and exporters at North Carolina’s ports

also saves them money. “Their ease of use is a factor for us,” explains

Chris Ahern, a spokesperson for Lowe’s Companies in Mooresville. “That makes

it more affordable.” Her company imports a range of items through Wilmington,

including lawn and garden items and lighting products. “The port is very

customer driven, flexible and easy to work with,” Ahern says. “We’ve used

the port for years and will rely on it even more as our imports grow.”

Setting Sail to New Markets

While customer focus has given the ports an edge over the competition, the same

hasn’t always been true when it comes to marketing savvy. While formally

operating under the umbrella of state government, the ports rely on internally

generated revenues to fund operations. That puts the burden on port officials to

constantly cultivate new users. Recent years have witnessed a renewed energy on

the part of the ports to aggressively court potential customers and shipping

lines.

“Marketing had been somewhat random because there wasn’t really good

data,” says Rob Gerlach, an organizational development consultant with the VTA

Group in Wilmington. In 2002, Gerlach began working with port leaders on

strategic planning and management effectiveness. Much of the ports’ business

development efforts were frustrated by insufficient resources, he says. But with

his help, marketing became an enterprise-wide objective, with cross-functional

leadership teams sharing perspective that had rarely been considered previously.

“They significantly improved employee knowledge about the business,” Gerlach

says.

As a result of the strategic planning initiative, port business developers now

mine a rich database of worldwide shipping data to identify ready marketing

opportunities. “What was once a shotgun approach to finding new business is

now highly targeted,” adds Gerlach.

Much of the Ports Authority’s business development vision centers on Europe.

Since 1997, neither Wilmington nor Morehead City has been served by a direct

shipping route to Europe, a reality that continues to slow business growth.

Beard Hardwoods, for example, must ship its Italy-bound products through

Norfolk. “We’re interested in securing any new services we can,” says

Glenn Carlson, managing director for business development at the Ports

Authority. Winning a European route is a challenge given that growth in global

shipping is largely concentrated on service to Asian markets. “There’s not

as much interest in carriers adding service to Europe,” he says.

Still, Carlson and his colleagues are putting the word out that North

Carolina’s ports are a viable option for Europeans looking to penetrate U.S.

markets. South American lines may also be good candidates, he says. His

conversations with shipping executives reveal interest on their part in North

Carolina, though none have yet pulled the trigger on initiating routes to

Wilmington or Morehead City. “It’s a slow process,” Carlson says. A little

luck could also help. “It’s a matter of getting in front of them at the

right time.”

Improving Infrastructure Improving Infrastructure

Recent improvements at both ports should go far in making each more marketable.

While not a container port, Morehead City’s bulk and break-bulk capacity is

proving a selling point. With the worldwide move toward containerization, many

competing ports dismantled facilities for handling bulk and break-bulk cargo.

Now, as a growing economy drives demand for basic materials, some see renewed

opportunity for Morehead City. Given the rise in steel prices, imports of scrap

steel through the port are fueling vigorous activity at Nucor Corp.’s new

recycling plant in Hertford County.

Morehead City, in fact, is now America’s second largest importer of raw rubber

(only New Orleans unloads more). The product arrives from Malaysia to Morehead

City in bins, eventually making its way via truck and railcar to top tire makers

such as Goodyear and Firestone. Moving the product has been a learning

experience for port workers, but they have risen to the occasion. “Raw rubber

is very perishable and not at all easy to handle,” explains Futrell, the

authority’s chair. “But our people have become expert at working with it.”

With a depth of 45 feet, Morehead City can handle the heaviest ships, and the

location of its piers just three miles from open seas gives it another edge.

More than 200 acres at adjacent Radio Island is ideal for industrial use or port

expansion. The Morehead City complex’s one nagging weakness is poor highway

access. Trucks must make a Jobian trek through scores of stoplights along U.S.

Highway 70 before reaching I-95 — more if they’re heading to Raleigh. “The

key to any port is getting cargo in and onto a ship quickly and efficiently,”

explains Frank Sheffield, an attorney with Ward and Smith in New Bern and chair

of the Ports Advisory Council. The panel is comprised of port customers and

business partners. “Unfortunately, there are no easy solutions to the access

challenge at Morehead City.”

But the situation can be improved, Sheffield says. Plans are on the books to

construct bypasses around Clayton, Goldsboro and Havelock. Once that occurs,

trucks will be able to reach the port with greater ease. Hastening those

improvements and others is a transportation project committee recently formed

under the auspices of Sheffield’s advisory group. “The idea is to muster the

statewide political support to obtain funding needed to complete those

projects,” says Sheffield, whose advisory panel is also pressing the ports’

case with officials in Washington, D.C.

The committee would also work to address access challenges around the Wilmington

port. While I-40 brings North America to the Port City’s doorstep, clogged

thoroughfares make the last few miles to the port terminal slow going.

Transportation planners are seeking to relieve those pressures with two new

bridges across the Cape Fear River — one already under way north of downtown

and another, possibly a toll bridge, reconnecting just below the port complex. A

new I-140 expressway would conjoin the two spans along the Brunswick County side

of the river, ultimately providing seamless passage from I-40 to the port’s

doorstep.

The commercial boost to the Wilmington port is self-evident. “There would also

be benefits to public safety and to national security,” says Cong. Mike

McIntyre (D-7th District), noting the

value both ports provide in moving military personnel, equipment and supplies

during wartime. McIntyre is working to secure the needed federal funds to make

the access improvements, and says the upgrades are the logical next step for the

Wilmington port now that deepening has been completed on the channel. In

January, ships calling at the port were greeted by 42-foot draft, which they

have long needed in order to arrive and depart fully laden.

Since 1998, the federal government invested $196.4 million in dredging the

channel and making other infrastructure upgrades. State and local funds also

drove the $292 million effort. “This was a major project since my first year

in office in 1997,” McIntyre recalls. “We’ve seen tangible results all

around,” he says. Sand pulled from the riverbed, for example, was used by the

Army Corps of Engineers to bolster nearby shorelines.

Seeing a Broader Vision

The broader vision of McIntyre and other advocates of the Wilmington port is

bolder still. Regional transportation upgrades, including the completion of

I-74, from Richmond County to Wilmington, will pull Charlotte closer to the Cape

Fear. “There’s also the prospect of extending I-20 to the port,” McIntyre

says, a move that would connect southeastern North Carolina with Atlanta,

Birmingham and Columbia. “Economically, the benefits would be astronomical.”

Higher quality roads feeding into Wilmington also will lend a hand to a

regionwide strategy to cultivate opportunities in retail distribution complexes.

“If you want to understand the opportunities that exist in that area, look at

Savannah,” suggests Steve Yost, a regional economic development representative

at the N.C. Department of Commerce based in Fayetteville. Born in the late

1990s, Savannah’s retail distribution strategy has attracted “big box”

retailers such as The Home Depot, Pier One Imports and Hugo Boss. The vision

transformed once-docile Savannah into the nation’s fifth busiest container

port. “The basic building blocks — mainly, ample and affordable land, a

strong labor force and a container-ready terminal — are in place for us to see

equally exciting results here,” says Yost.

Yost and his colleagues at Commerce, local economic developers and officials of

North Carolina’s Southeast Commission are now teaming up with port officials

to market the region’s appeal as a destination for import-oriented retailers.

Wages in the industry stack up nicely with those paid by manufacturers, and

distribution operations are natural resource-friendly, according to John Swope,

executive director of the Sampson County Economic Development Commission.

“Unlike a process industry, they don’t consume huge amounts of water and

sewer capacity,” Swope says.

Earlier this year, Swope and others associated with the Southeast’s

distribution strategy unleashed a one-minute video email to 2,500 retail

executives, logistics firms and site consultants, offering them a graphics-rich

overview of what the region offers their industry: quality lands, two existing

interstates and another on the way, generous incentives and more. The following

month, they set up a booth at an Orlando trade show for logistics leaders.

“The email drove a lot of traffic to our booth,” says Kristy Smitherman,

marketing director for North Carolina’s Southeast Commission in Elizabethtown.

The region has set its sights on large, technology-driven distribution

operations, she says, which can employ hundreds of workers at healthy wage

levels. “There’s a misconception that distribution projects don’t spur a

valuable economic impact,” Smitherman says. “The larger ones clearly do.”

Ed Church, who recently was hired as the ports’ economic development director,

is encouraged by the reception the authority has received in its outreach to

local, state and regional economic developers — on retail distribution and

other initiatives. “One of the successes we especially admire at Savannah is

their strong economic development alliances,” says Church, who was previously

a county developer and Commerce regional development officer in Charlotte. “We

have the ability to pool our resources here, too, and make companies aware of

the resources we have.”

North Carolina’s ports are shedding their undeserved reputation as bit players

in the state’s economy, and their timing couldn’t be better. With trade

activity helping usher the nation’s economy out of recession, business at

Wilmington and Morehead City is brisk. And now that infrastructure and

organizational improvements are kicking in, the world may finally be ready to

take note.

“I think North Carolina is sitting here with a golden opportunity,” says

Louise McColl, vice chair of the Ports Authority and a member of NCCBI’s

executive committee. “A lot of great things are beginning to happen at both

Morehead City and Wilmington.”

Until about five years ago, the ports were perhaps the state’s most

underutilized business assets, she recalls. “We’ve got the right people

focused on the right issues,” she says of the Ports Authority’s leaders and

allies.

Higher

Gas Prices Drive Many to Find -- And Enjoy -- Mass Transit

Randy Wheeless doesn’t mind his

half-hour ride to work. Along the 12-mile trek between his home near Mint Hill

and Charlotte’s Uptown, the senior communications specialist for Duke Energy

scans the morning paper and catches up on a backlog of news magazines. All the

while he’s saving himself real cash and making the Queen City a more

breathable place to live and work.

Even before gas prices stretched into the stratosphere, Wheeless was taking the

bus to work. “The roundtrip works out to $2.50 each day,” he says.

Considering the savings in fuel and garage parking fees, he comes out ahead.

That is largely because his employer offers cut-rate public transit tickets in

order to encourage alternatives to single occupancy commuting. As the air in and

around North Carolina’s urban centers becomes smoggier, it is a benefit more

and more employers are willing to provide.

Since the 1990s, air quality has become a concern for Research Triangle Park

companies trying to recruit top talent. But now that the U.S. Environmental

Protection Agency (EPA) has cited Raleigh-Durham for “non-attainment,” the

pressure is on to find workable alternatives to the common sight of workers

motoring to the office solo. “Now the EPA is making the rules, and they will

withhold and re-direct transportation dollars,” explains Pam Wall, executive

director of the Greater Triangle Regional Council, a nonprofit group working to

resolve environmental and other functional challenges facing the region. “We

have to have a plan in place by 2007,” Wall explains.

Employers are following the lead of Duke by offering cut-rate transit tickets.

Some are even opening their flexible employee benefits programs (e.g.,

“cafeteria plans”) to workers, who can pay for mass transportation with

pre-tax dollars. At IBM, workers get subsidies when joining van pools, and the

company reserves priority parking for carpoolers. It is also installing bike

racks and shower facilities to accommodate those interested in pedaling to work,

according to Susan Clarke, an environmental engineer at the company’s RTP

site. In addition, the company encourages telecommuting, when practical, and is

supporting efforts to build a light rail system around the Triangle, Clarke

says.

IBM is one of 20 RTP employers participating in SmartCommute, a program begun in

1999. It offers a venue through which employers, transit services, and state and

regional transportation officials can develop workable commuting alternatives.

One example of their collaboration: an emergency ride home program for

carpoolers who suddenly find themselves needing to leave work early. “The

service is needed on very rare occasions, but it provides that bit of assurance

that some really find important,” says Julie Woosley, SmartCommute’s

director. The program (www.smartcommute.org)

also helps connect non-member firms with the knowledge they need to start a

commuter benefits program. The N.C. Department of Transportation, for instance,

offers free one-day classes for interested employers, she says.

IBM and Duke are among the handful of North Carolina employers listed nationally

as Fortune 500 “Best Workplaces for

Commuters.” The citation honors employers offering outstanding commuter

benefits. Regional versions of the program, which is sponsored by the EPA and

the U.S. Department of Transportation, are now being organized in

Charlotte-Mecklenburg and the Triangle. Houston, Tucson, San Francisco and New

England have implemented similar regional efforts, and firms there have seen

employee participation rates steadily grow.

About 15 percent of RTP employees take advantage of commuting alternatives,

Woosley’s surveys show. Woosley rides a TTA bus to work two to three times a

week. Her 40-minute ride from North Raleigh to the Park is spent reading and

responding to email on her laptop, she says.

Duke Energy has joined with Charlotte Area Transit System (CATS) in sponsoring

regular educational sessions on transportation options. Randy Wheeless has begun

to notice more Uptown bound professionals hopping his morning bus. “Once

people try it out, they realize it’s not a bad way to go,” he says. — Lawrence

Bivins

Return to magazine index

|