|

Read our Q and

A

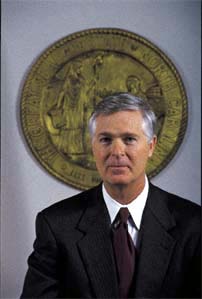

with the new governor

Meet Mike Easley

The

new governor is a complex individual,

a

shrewd politician who also is a shy family man

Having

become comfortably accustomed to governors whose personalities and

politics – even their names — were as familiar as a well-read

book, North Carolinians are about to roused into attention by the man

who next will occupy the Governor’s Mansion – if and when he

decides to actually move in.

Michael F. Easley, the Democrat and two-term state attorney general

who defeated former Charlotte mayor Richard Vinroot on Nov. 7, might

be one of the most complicated, contradictory figures ever to become

the state’s chief executive. He will be sworn in on Jan. 5 to

succeed four-term Gov. Jim Hunt.

On the one hand Gov.-elect Easley, 50, boasts a biography that’s a

Tar Heel classic. He grew up on a tobacco farm in Nash County, the

second of seven children who all got good educations and went on to

better things. He lettered in football at Rocky Mount High School;

received an undergraduate degree, with honors, from Carolina in 1972;

and earned a law degree, cum laude, from N.C. Central in 1976 while

serving as managing editor of the Law Review.

Six years out of law school he was elected district attorney in

Brunswick, Bladen and Columbus counties, and quickly attracted

attention for his aggressive prosecutions of South American drug

traffickers. USA Today named him one of the nation’s top

“drug-busters” for helping convict 40 members of the notorious

Shagra-Piccolo Gang, the outfit that had assassinated a federal judge

in Texas. One of the drug-runners put out a contract on Easley’s

life, and for a time he carried a loaded handgun in his glove

compartment; Easley also kept a shotgun at his Southport home and

taught he wife how to use it.

He first sought statewide office in 1990 when he ran in the Democratic

primary to oppose Republican U.S. Sen. Lauch Faircloth, but lost to

Harvey Gantt. Two years later he ran for state attorney general and

breezed into office with the highest-ever vote total of any candidate

for state office. He was the state’s top vote-getter again in 1996

when he coasted into a second term with nearly 60 percent of the vote.

Last May he ran against popular two-term Lt. Gov. Dennis Wicker in the

Democratic gubernatorial primary, and even though he didn’t have the

backing of the party’s old guard, as Wicker did, and even though he

raised and spent about $1 million less than his opponent, Easley won

easily.

But

on the other hand, as a person and as a politician Easley is unique in

the state’s modern political history, beginning with the fact that,

unlike the born-again Baptist, Methodist and Presbyterian governors of

the past, Easley is a practicing Roman Catholic who attended an

integrated parochial school as a child. And as far as anyone knows, he

will be the state’s first governor with a learning disability.

When he was at Carolina it became clear that Easley had a problem

reading books and retaining information about what he had read.

Classmates helped by reading textbooks to him, and he developed an

astonishing ability to remember what he heard. He has since mostly

overcome the disability but he still has an aversion to printed

materials and prefers oral reports and voice mail.

(Two years ago when he and several other state attorneys general were

negotiating the $206 billion national tobacco settlement in New York,

Easley was the only participant not seen carrying a briefcase bulging

with legal papers. Each night after the proceedings he would have

aides read the filings to him, and he relied on a near-photographic

memory to cite chapter-and-verse details during the next day’s

talks.)

Then there’s Easley’s penchant for biting the political hand that

feeds him. Throughout his career he has never embraced, nor been

embraced by, the Democratic Party machine, most notably when he took

on Wicker, the party’s heir-apparent for governor. That pattern

began when, as a district attorney, Easley vigorously prosecuted 34

public officials, most of them Democrats who had helped get him

elected, including a state legislator, a well-liked clerk of court and

two of the three sheriffs in his district.

And he seldom goes along to get along, even with his political mentor,

powerful state Sen. Tony Rand (D-Cumberland). In 1997, when Sen. Rand

introduced legislation to allow Blue Cross and Blue Shield to convert

to a for-profit company, Easley threw a monkey wrench in the works by

offering his opinion as attorney general that the state’s largest

insurer belonged to the public.

But

what mostly makes Easley a very different politician is that he simply

doesn’t like politicking, particularly the back-slapping,

barbeque-eating brand of retail politics that long has been a staple

of North Carolina campaigns. He comes off as a bit lawyerly when he

addresses large crowds and he can be aloof at times. But in small

groups he is warm and personable.

(During the interview for this story, for instance, he was cautious in

his remarks and reserved in his demeanor. But when he learned that the

photographer who was taking his picture also was from Rocky Mount and

that they had several common acquaintances, Easley immediately warmed

up and soon had everyone laughing at old Nash County stories.)

If Easley is a bit stiff on the stump, there’s no doubt that he’s

a natural for television. With his penetrating blue eyes and graying

temples, he looks great on TV and has the anchorman’s ability to

look through the camera and connect with viewers – a talent he used

to great advantage during the gubernatorial campaign.

Despite

his occasional unpredictability and his past differences with the

Democratic political mainstream, Easley was elected governor on a

platform built on traditional party themes. The two major issues he

ran on – education and economic development – are pages straight

out of Jim Hunt’s playbook. But Easley did break ground on at least

one new issue. For the first time, a governor of North Carolina says

the state should have a lottery.

Easley’s top educational priority is reducing class size in

kindergarten through third grade to no more than 18 pupils. Hiring

enough additional teachers to accomplish that would cost anywhere from

$120 million to $200 million a year. With the state facing a revenue

shortfall of as much as $300 million in the current fiscal year, and

with tight finances predicted for the next several years, Easley must

find a new source of revenue to pay for his pet project. He thinks a

lottery is the best way to do that.

“We’re the only state in the county that plays the lottery and

leaves the money on the table,” he says in the accompanying

interview. That’s mainly because thousands of North Carolinians

cross the state line to play Virginia’s lottery, he says. And now

that South Carolina voters have approved a lottery, North Carolina is

“the hole in the doughnut,” surrounded by lottery states.

Otherwise, Easley is expected to focus on many of the same issues as

Hunt did over the past eight years and to continue the solid,

bipartisan relationship with the General Assembly as his predecessor.

If there is a clear distinction between Hunt and Easley it is that

Easley embraces more populist themes, as witnessed by his record as

attorney general attacking predatory lending practices and other

consumer initiatives. However, he can take a conservative tact at

times, as when he fought the federal courts – and won -- over

overcrowding in state prisons, a victory that kept 4,000 felons behind

bars.

Another distinction is his night owl work habits. According to several

published accounts, Easley usually retires at 10 or 11 p.m. and gets

back up at 1 in the morning and works through the wee hours – often

startling people who get long voice mail messages from him in the

middle of the night. He goes back to bed around sunrise for a long nap

before beginning the work day. But he frequently tires during the day

and often works from home. He has been criticized for keeping an

irregular work schedule.

Mike

Easley also is very much a family man. His widely-reported reluctance

to move into the graceful but aging Governor’s Mansion apparently

stems from real concerns about whether his wife and 15-year-old son,

Michael Jr., could maintain a normal family life there. His wife,

Mary, is a native of New Jersey and a working mom who has a tough

commute to her job teaching law at N.C. Central – a commute that

would be longer and harder if she had to start from downtown rather

than the Easley’s current home near the Raleigh beltline.

The Easleys also own a home

in Southport and, together with one of his brothers, a condo on Bald

Head Island. Easley is an accomplished woodworker, an avid duck hunter

and sailor.

Return to magazine index

|